When I go through the piles of vintage children’s magazines I’ve collected over the years, one thing strikes me. Kids don’t read this kind of stuff anymore. They probably don’t read at all, but the historical and classic tilt to the John Martin’s Book, The Child’s Magazine, may be over the heads of most children today. I realize we are supposed to be more educated, technically advanced, better off than back in 1912 when this man began his publishing, but as far as what kids were expected to know, expected to learn, expected to memorize in the past, education has been dumbed down, or in nicer vocabulary, simplified.

Up until I just googled him, I knew very little about the man behind these extraordinary publications. I knew his real name wasn’t John Martin, although I could never imagine such an interesting one as Morgan van Roorbach Shepard. His life reads like an adventure story, or a tale from Dickens. He was born in Brooklyn, and grew up on a plantation. Right here, the story seems implausible. For some reason, he decided to retain the last name of the either a ‘colony’ of people named Martin, or bunches of birds–wiki doesn’t explain. Devastated by his mother’s death when he was nine, he was shunted off to boarding schools. According to wikipedia, he was often bullied, but considering the new popularity of that word, I have my doubts as to what that means. I also don’t know what, if anything, suffering in boarding school like most kids who attend, did to form his character. He told a tale of being a revolutionary in some South American country, was fired as a conductor on a San francisco trolly car for giving free rides to children and specific adults, and began his own greeting card company in a building destroyed by the famous 1906 earthquake, in which he was injured. Supposedly it was during his convalescence he began writing stories and poems for children, which after several years became long illustrated letters to thousands of kids, and in 1912 became the magazine.

never imagine such an interesting one as Morgan van Roorbach Shepard. His life reads like an adventure story, or a tale from Dickens. He was born in Brooklyn, and grew up on a plantation. Right here, the story seems implausible. For some reason, he decided to retain the last name of the either a ‘colony’ of people named Martin, or bunches of birds–wiki doesn’t explain. Devastated by his mother’s death when he was nine, he was shunted off to boarding schools. According to wikipedia, he was often bullied, but considering the new popularity of that word, I have my doubts as to what that means. I also don’t know what, if anything, suffering in boarding school like most kids who attend, did to form his character. He told a tale of being a revolutionary in some South American country, was fired as a conductor on a San francisco trolly car for giving free rides to children and specific adults, and began his own greeting card company in a building destroyed by the famous 1906 earthquake, in which he was injured. Supposedly it was during his convalescence he began writing stories and poems for children, which after several years became long illustrated letters to thousands of kids, and in 1912 became the magazine.

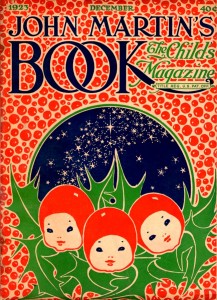

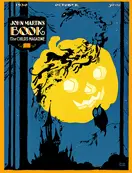

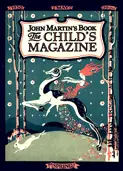

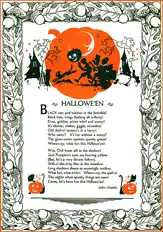

I first came across the magazines on eBay, back when eBay sold vintage items, and wasn’t a warehouse for cheap new stuff. I collect vintage Halloween, and was searching for magazines with that holiday’s covers. Vintage Halloween was a hot commodity back then, and fierce bidding could occur over one piece, be it crepe paper or magazine. I managed to snag a few, and while perusing other months of the magazine, realized how amazingly cool they were. The illustrations were astonishing, the stories long and detailed, the entire package, from front cover, to back advertisement, was designed to compliment whatever theme that month had. Most months were geared to holidays within, others would have generic covers of children playing etc. All were exceptional. Thus began my acquisition of as many as I could afford–and more importantly–find. They aren’t plentiful, at least

not in my experience. I’ve been to ephemera and book/paper shows, and not one copy of a John Martin’s appeared. I believe the reason for this is the quality of paper used. Age has browned them to a dark goldish tan, and they flake, crumble at the merest rough touch. The magazines may not have survived as well as other publications from 1912 through 1933. I also believe that the quality of work within may have contributed to the pieces being handled quite a bit and perhaps even passed down generations until finally became too brittle to keep. I have a small but nice collection. A man on eBay may have the entire run by now, if he has continued collecting since I met him back in 1998. His goal was to acquire pristine copies of one of each magazine. That’s a lot of magazines, and to find them without crayon, paper-dolls cut, front and back covers missing, is a real challenge. Many of my copies are missing covers. That’s how rare these things are seen–sellers who don’t know what they’ve got mistake the gorgeous magazine endpapers for front and back covers.

not in my experience. I’ve been to ephemera and book/paper shows, and not one copy of a John Martin’s appeared. I believe the reason for this is the quality of paper used. Age has browned them to a dark goldish tan, and they flake, crumble at the merest rough touch. The magazines may not have survived as well as other publications from 1912 through 1933. I also believe that the quality of work within may have contributed to the pieces being handled quite a bit and perhaps even passed down generations until finally became too brittle to keep. I have a small but nice collection. A man on eBay may have the entire run by now, if he has continued collecting since I met him back in 1998. His goal was to acquire pristine copies of one of each magazine. That’s a lot of magazines, and to find them without crayon, paper-dolls cut, front and back covers missing, is a real challenge. Many of my copies are missing covers. That’s how rare these things are seen–sellers who don’t know what they’ve got mistake the gorgeous magazine endpapers for front and back covers.

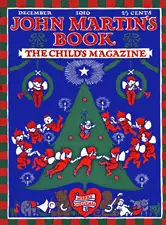

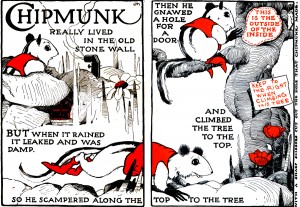

So what inside makes these magazines seem to be of a higher educational quality than what kids are exposed to now? One blatant thing–poetry, tons of kid’s poems. Books from that time frame seem full of poems. Each John Martin’s Book has at least one poem, if not several. I don’t know if a kid today is exposed to poetry, other than rhyming Dr. Seuss. Another vast difference–entertaining stories touch upon history. My December 1920 has a tale of the Mayflower. Another illustrated story explains dentistry, through humor. There is an explanation of how mistletoe came to be associated with Christmas, which involves myths. Each magazine has loads of animal tales, real wild ones, and cute fantasy stories. And puzzles. Word puzzles, visual puzzles. Simple word associations via fantastic pictures. Even the ads are full of stories and illustrations–sometimes they can’t be distinguished from the bulk of the magazine unless you pay close attention to the brand name. The back cover of the 1920 Christmas issue is a  continuation of the front–except on back is a Colgate ad. The indication of this–elves are holding tubes of paste on the side, and below a poem written for the kids about the magazine itself, the Colgate brand name is stated. The magazine is for small kids, and slightly older ones. According to wikipedia, it’s for ages 5 to 8 year olds. If that’s true-8 year olds sure could read incredibly well, because the stories are not simple ones. They are complicated and full of words I don’t associate with kids that young. Maybe I’m

continuation of the front–except on back is a Colgate ad. The indication of this–elves are holding tubes of paste on the side, and below a poem written for the kids about the magazine itself, the Colgate brand name is stated. The magazine is for small kids, and slightly older ones. According to wikipedia, it’s for ages 5 to 8 year olds. If that’s true-8 year olds sure could read incredibly well, because the stories are not simple ones. They are complicated and full of words I don’t associate with kids that young. Maybe I’m

completely out of sync with what kids can read at that age. I suppose I could be, but I don’t remember reading things such as this at 8. There is absolutely no wasted space within each issue–every penny spent is worth it–and it cost up to 50 pennies at one time–which means only middle class and upper class kids were able to peruse. Nothing different there. John Martin would write a letter to the readers, printed at the beginning of each issue. I suppose this was a leftover from when the entire thing was in the form of a letter. And make no mistake, this was a very American, patriotic, Christian publication. Each holiday was celebrated–from George Washington’s birthday, to May Day, to a religious Christmas. At all times the tone of the book was cheerful, studious, entertaining, and of high quality.

And then there are the illustrations. A candy store of delicious pictures. From the hands of famous artists such as: Dorothy P. Lathrop–whose animal pictures in the Dec. 1920 issue surprised me–Thornton Burgess–known for his work with Harrison Cady, and Johnny Gruelle–famous for Raggedy Ann and many more books. Lesser known artists populate each issue, some that will never be recognized because either they didn’t sign the artwork, or the initials they leave aren’t enough to discover who they were. There is a wonderful illustration for a Super Coaster ad in the back of an issue–Santa Claus is filling a wagon with goodies. Not an wisp of an initial to be found. Whoever created this lovely illustration is lost to the ages. There is an unsigned illustration and poem for a date company–as in fruit–no the magazine wasn’t advocating children start dating. Another poem has an adorable illustration by an artist I’ve never heard of, Winifred

Ackroyd–but that’s the usual within the magazine–so many artists helped make the issues a “pioneering publication” and the “most entertaining magazine” directed at children in 5 to 8 age group in the US according to scholar Martin Gardner. George Carlson was the most prolific–he was responsible for the Peter Puzzlemaker games within each magazine for many years. He also illustrated stories, ads, poems, and most strikingly, the front covers. Some of the best Halloween artwork came from Carlson. He later created the dust jacket for Gone With the Wind, and various cartoons. For some reason, his work on John Martin’s Book seems to have been lost to people like Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr., whose fantastic website showcases Golden Age Illustrators and more. And his name doesn’t gain recognizability unless one is a collector of John Martin’s or vintage Halloween. What a shame.

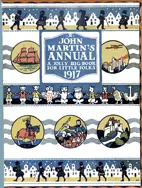

In addition to monthly issues, John Martin’s would publish an compilation of the best features of that year. Most people I know who have heard of John Martin’s Bookdo so

because of these large thick volumes of reprinted stories and illustrations. I own a few, and they are marvelous. But the print quality of the original magazine cannot be matched. I would have scanned some illustrations from the issue I sited in the article–but it’s one of the few copies I own that is in pristine condition, and I don’t want to jeopardize it.

The magazine stopped publication in 1933. Why? My guess would be the depression. No money to spend on non-necessities. According to wikipedia–in 1920 there were 45,000 subscribers, by 1932, only 23,00. There is no stated reason for the closure, but lack of funds surely played a huge part. During the entire run, his second

in command was Helen Jane Waldo, whose contribution cannot be measured, as the facts surrounding this once highly regarded and popular magazine seem foggy at best, obscure at worst. Again, from Wikipedia–the only place that seems to have any info on this subject–John Martin’s next venture was as a juvenile director for NBC–which was a radio company at the time, my guess. There is nothing after that about him. He was born in 1865 and died in 1947. At 82? (I have no math skills)

The legacy of John Martin’s Book may be unseen by most, but I believe it is there. Years ago I was bidding on a copy, and noticed the name of a person who was bidding against me–you could still see these things back then. I e-mailed the lady, asking politely, but with excitement, if she was the writer and wife of Michael Hague, the celebrated illustrator of children’s books, whose work includes new versions of Alice in Wonderland, Mother Goose, and his wife’s Teddy Bear books. She replied, saying he often uses old material such as John Martin’s for inspiration. I was thrilled that not only had I had contact with someone I admired, whose husband’s work is fantastic, but that my love of an ancient, brittle, unknown publication was held in esteem by a modern age renowned artist. I believe the influence of The Child’s Magazine is alive and well, and may continue for years and years to come.