by Jas Faulkner

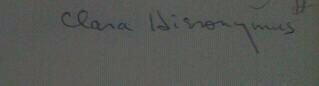

It was one of those finds in the LitCrit section of McKay’s Books that looked like a good cold weather read. Playing Joan is an anthology of interviews with actress who have played the Shavian heroine over the years. The book looked like it was nearly new and had never been read. At $1.50, it was a deal. Then I noticed there was a name written on the title page.

It was one of those finds in the LitCrit section of McKay’s Books that looked like a good cold weather read. Playing Joan is an anthology of interviews with actress who have played the Shavian heroine over the years. The book looked like it was nearly new and had never been read. At $1.50, it was a deal. Then I noticed there was a name written on the title page.

Before I get into that, I need to make an admission. I’m one of those people who loves finding old things in books. By old things, I don’t mean the dessicated corpses of insects or antique Fritos. I’m talking about postcards, invoices, ticket stubs, newspaper clippings and class schedules. They give me a clue about who read this book before it fell into my hands. I’m also a fan of old library book discards. It makes my shelves feel well-traveled.

More often than not the name written the front of a book offers little information about the former owner. I will occasionally see a prominent Nashville surname or the scrawled ex libris of a former teacher, but usually the monikers are fairly unknown to me. That was not the case with the copy of Playing Joan I held in the aisles of the UBS. The name on the title page belonged to someone who most likely could have spoken to the subject with an authority that would have put many of the literary lions at Vanderbilt to shame.

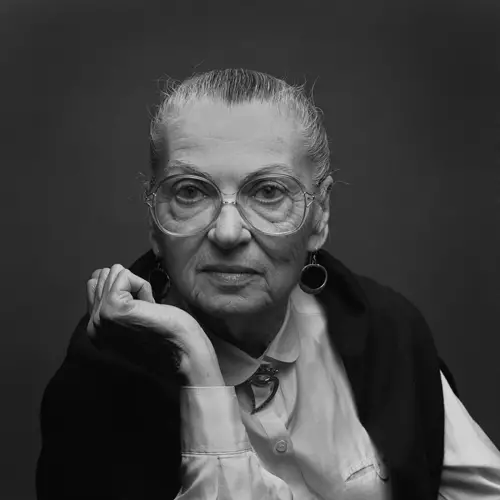

Clara Hieronymus. For over forty years, artists, musicians and thespians faced her owlish gaze as they presented their best, hoping for a critical nod from Nashville’s grande dame of arts reporting. Her reviews were full of brio and wit. Even if the event in question was of no interest, her opinion was always worth the cost of a copy of the Tennessean and the time it took to read it.

As a teenager with literary ambitions, reading and learning from Ms Hieronymus seemed like a smart thing to do. It wasn’t until college that I learned her influence went far beyond the readership of Nashville’s paper of record, The Tennessean. She was a founding member of the American Theatre Critics Association.

college that I learned her influence went far beyond the readership of Nashville’s paper of record, The Tennessean. She was a founding member of the American Theatre Critics Association.

She might have intimidated many actors and directors in her day, but she also served as one of the city’s more vocal advocates. Thanks to her writing, those who would have dismissed Nashville as an unsophisticated backwater reconsidered the arts and letters that originated from Middle Tennessee.

Looking at the book in the aisle at McKay’s, I noticed that it was barely shelfworn. Either Ms Hieronymus was a very careful book owner or this was a volume she’d accepted as a perusal copy and had not read or possibly had only read the interviews that interested her.

I would have bought the book anyway, but I wondered if some theatre enthusiast might have snapped it up for no other reason than the identity of the previous owner. People who insist on owning artifacts of other people’s lives have always alternately fascinated and confused me. In a way, I get being a fan, and yet there is also the obstinate part of me that gets restless at the thought of dedicating so much energy to the observation of other lives. Even if it isn’t the case, sometimes it feels like this sort of thing happens at the expense being an active participant. Would I rather write about someone else’s theatre or write my own plays? Would I rather write about watching a hockey game or write about lacing up and getting on the ice? Would I rather read about art or paint my own pictures?

When I told friends about the book, particularly those who are my age and older and who are fellow alumni of Nashville Children’s Theatre, the reaction was almost always something to the effect of having Miss Clara’s critical mojo at my disposal. I don’t really believe that any more than I believe owning one of David Legwand’s old sticks will make me a great center. I know, even as I write this, there are people who feel that owning artifacts from those full, wonderful lives will make their own just as great. Maybe the true alchemy of that kind of proximity is that it reminds us of the potential we all have for creating our own magic.