by Jas Faulkner

At a recent gathering of oral historians and archivists, the subject of data retrieval long after collection came up. Hard copies, acetate based media, anything mechanical, was still alive as far as many curators were concerned. However, when it came to digital media, the prospect of anything outliving its technology was far less likely.

One archivist recounted discovering that she needed to find an engineer who could help her recreate the the technology needed to rerecord interviews that had originally been stored on cylinders. Finding a person who could do this via word of mouth took roughly two weeks. Once the material was retrieved it was archived in a way that assured that the content of the interview would be accessible regardless of future technological changes: a paper transcript was created and carefully stored. The kicker came at the end of the month when the archive’s administrators refused to reimburse the personnel who elected to bring in the technician. The administration’s argument was that a perfectly good digital copy had been made and should have sufficed when the need arose to retrieve the recording.

The date written on the 3.5 floppy disc in question was May, 1998. None of the computers in the archive or in the building housing the academic department it trains had a drive that could read such a disc. The computer science department had a drive, but there was no program or driver available to enable it to read the disc’s contents. Had the scratchy, primitive cylinder not been around, and the engineer had not been found who could manipulate the relatively simple mechanics to get the audio document, it would have been lost forever.

The date written on the 3.5 floppy disc in question was May, 1998. None of the computers in the archive or in the building housing the academic department it trains had a drive that could read such a disc. The computer science department had a drive, but there was no program or driver available to enable it to read the disc’s contents. Had the scratchy, primitive cylinder not been around, and the engineer had not been found who could manipulate the relatively simple mechanics to get the audio document, it would have been lost forever.

Loss of materials due to technological obsolescence is not new, nor is it limited to the aegis of historic or scientific preservation. Twentieth Century film historians wrestled with the frustration of trying to find and restore movies that are lost except for the news accounts of the films and the few stills that can be found in studio archives. Political shifts and cupidity are also culprits when it comes to maddening gaps in the oeuvres of individuals and in some cases, entire groups. Nothing brings out hours of undiscovered footage like the death of an artist.

Our appetite for entertainment has not waned, but the media of choice and the industry’s approach to ownership certainly has. It’s not that fans no longer see the value in spending money on hard copies but rather that the content itself has become a quasi-utility. The popularity of services like stubhub prove fans will pay more to experience content live, be it music, plays, comedy or sports. Polls of consumers who formerly bought hard copies of music, movies and television series are now opting to pay monthly fees for access to extensive streaming libraries such as the ones maintained Spotify, Netflix, and Amazon. As the next generation comes of age, the idea of owning a hard copy of any kind of entertainment media will seem quaint, antiquated, the stuff of geek subcultures.

This brings up some interesting questions regarding e-publishing. The debates about DRM material are dividing consumers, who are caught in what sometimes looks like a race to the bottom as they choose a reader they hope will be supported for years to come. In the meantime, writers are finding self-publishing is no longer a stigmatised no man’s land full of marginally talented hacks flacking bad books. Authors are taking a similar route to musicians and using self-publishing platforms that not only cut overhead costs, but almost completely eliminate the middle man.

There have been assurances that “books will never go away”. This is more than likely true. It is possible that in the near future there will be paper books but they will be harder to get than their online counterparts. Libraries will be reduced to a token shelf of paper curiosities while the future iterations of hand-held devices will contain hundreds, possibly thousands of books. Progress is progress and it stands to reason that as things move to ones and zeroes as opposed to ink and paper, the meta-artistry will follow and we will see beautiful electronic books that are every bit as artful as the paper tomes that preceded them. What happens when technology changes? Do the works that have not migrated to new media go a step further into obscurity than old books from bygone days?

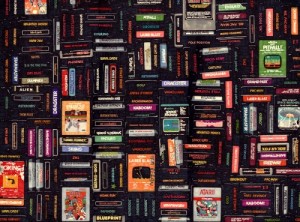

The answer may be found in the example set forth by fans of old video game

The answer may be found in the example set forth by fans of old video game  systems. Once considered long dead artifacts of the seventies and eighties, anthologies of games that were originally designed for Activison, Commodore Systems and Atari are brisk sellers. Fan of the original releases and new admirers of the feel and content of those games are giving them second and third lives. This might be a glimpse of the future for digital-only releases of what might have been small press books in a previous decade. In their own way, such revivals are hopeful signs . Still, it would be a shame for good books to submerge in the dark waters of lost technology, sitting unread for who knows how long, silent and dead to the eye and mind that could breathe life into their words.

systems. Once considered long dead artifacts of the seventies and eighties, anthologies of games that were originally designed for Activison, Commodore Systems and Atari are brisk sellers. Fan of the original releases and new admirers of the feel and content of those games are giving them second and third lives. This might be a glimpse of the future for digital-only releases of what might have been small press books in a previous decade. In their own way, such revivals are hopeful signs . Still, it would be a shame for good books to submerge in the dark waters of lost technology, sitting unread for who knows how long, silent and dead to the eye and mind that could breathe life into their words.

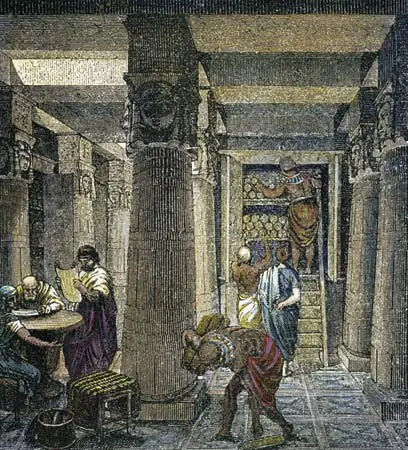

The sense of loss many book lovers feel when learning about the destruction of the Library of Alexandria is more often couched in the contemplation of what might have been lost. We have the means to prevent future works of art from becoming inscrutable blocks of plastic waiting for the right person to unlock their secrets. The original Rosetta Stone is a testament to ancient artistry and the collaborative scholarship of those who worked to decode it. It’s a bit of history we can appreciate without repeating.

This post spoke to me on so many different levels. As a geek, I advocate a forward thinking approach to keep old content up to the times. Older books should be adopted into the eBook age. Google has done a remarkable job of this to the chagrin of authors, publishers and a lot of other understandbaly angry people. Project Gutenberg does much the same thing without any of the uproar.

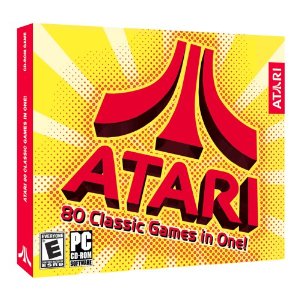

The Atari antholgy is the best example of this; all the best games we loved are available today. The publisher took the initiative. Authors and publishers should do the same thing.

The advantages are obvious; authors have a backlist with a shelf life of eternity. Publishers win in being able to sell inventory over and over again without having to fire up the printing press for another run.

This is the model I adopted from the beginning with — get this — the interactive fiction titles I write and publish. Now we get to the heart of why this article really reached me. Not so i could engage in some handy BSP but to share two passions of my own and how they resonate with everthing you said. If text adventure games and interactive fiction (think Zork) can thrive in the 21st century so can even the oldest of books.

Ditto that 3.5 inch floppy. If the data it contained was so important somebody should have had the insight to take that data by the hand and march it over on to a CD-R or DVD-R or, even more modern, a Blu-Ray disc.

We’ve all got to take a hand in keeping the content we cherish current with the times.

Agreed! And I love the idea of publication on demand for books!

This was a comment from Howard Sherman. We recently changed our commenting system at The Bookshop Blog and I didn’t want this to get lost. – –

This post spoke to me on so many different levels. As a geek, I advocate a forward thinking approach to keep old content up to the times. Older books should be adopted into the eBook age. Google has done a remarkable job of this to the chagrin of authors, publishers and a lot of other understandbaly angry people. Project Gutenberg does much the same thing without any of the uproar.

The Atari antholgy is the best example of this; all the best games we loved are available today. The publisher took the initiative. Authors and publishers should do the same thing.

The advantages are obvious; authors have a backlist with a shelf life of eternity. Publishers win in being able to sell inventory over and over again without having to fire up the printing press for another run.

This is the model I adopted from the beginning with — get this — the interactive fiction titles I write and publish. Now we get to the heart of why this article really reached me. Not so I could engage in some handy BSP but to share two passions of my own and how they resonate with everthing you said. If text adventure games and interactive fiction (think Zork) can thrive in the 21st century so can even the oldest of books.

Ditto that 3.5 inch floppy. If the data it contained was so important somebody should have had the insight to take that data by the hand and march it over on to a CD-R or DVD-R or, even more modern, a Blu-Ray disc.

We’ve all got to take a hand in keeping the content we cherish current with the times.

nice medicine……