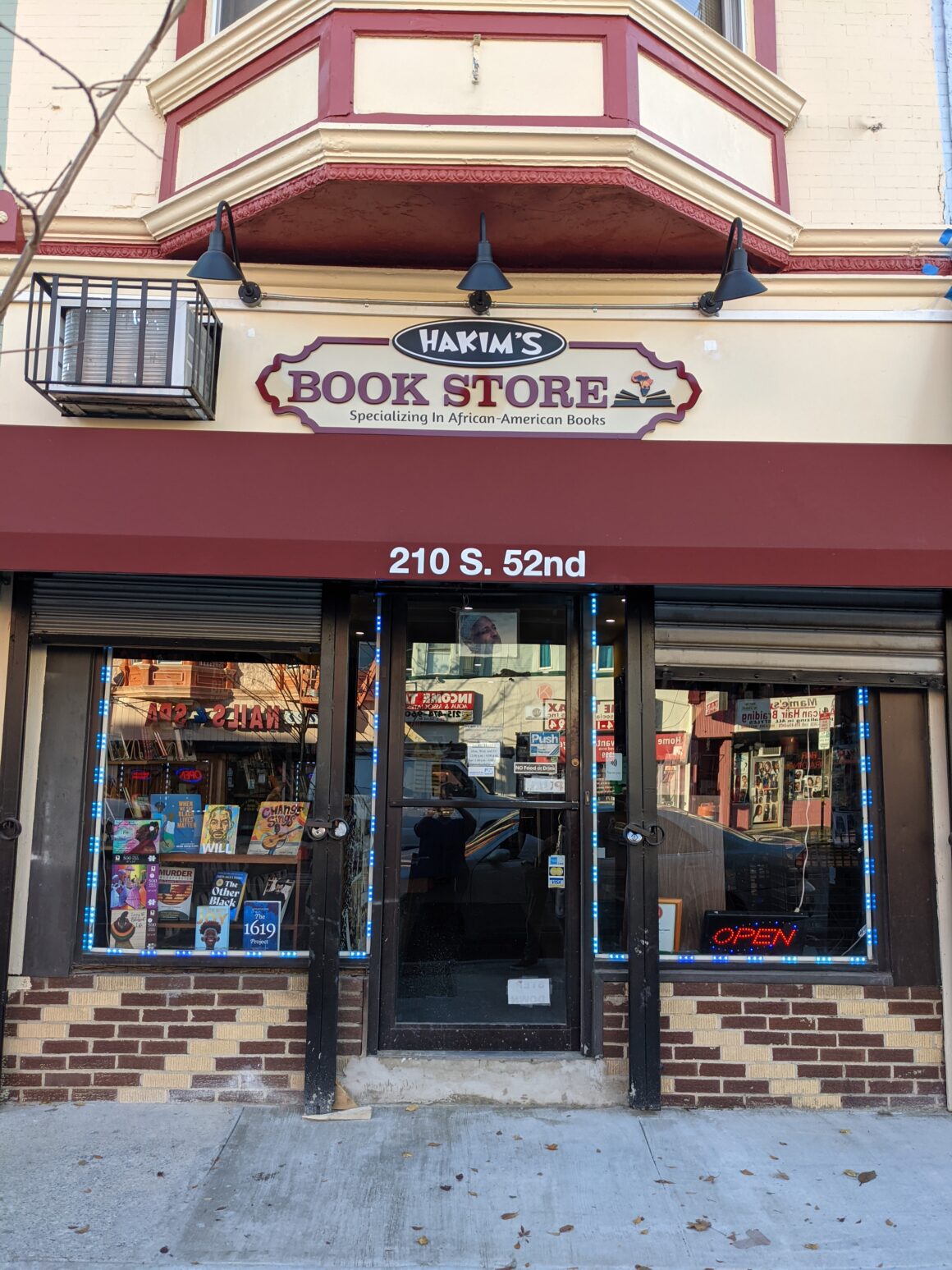

When Dawud Hakim opened Hakim’s Book Store in 1959, it was more because he was compelled to share knowledge with the wider community than because he saw an unfilled niche, although both were true.

Hakim was inspired by newfound knowledge.

“He became intrigued after he read some books by the author Joel Augustus Rogers, Five Negro Presidents and 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro,” said his daughter Yvonne Blake who owns and runs the shop today. “Once he started reading those books, he started looking into other books and looking into African American history, realizing that our history didn’t start with slavery and that there were books out there.”

Related: A Secret Passage and a Plan for the Future at Your Brother’s Bookstore

For context, while some people celebrated “Negro History Week” at the time, Black History Month wasn’t recognized nationally until 1976. As we all know from the headlines, a serious discussion about how to integrate American history as a whole wasn’t conducted until the 21st century. Hakim was among those who recognized the critical hole in our wider understanding of the black experience, even among black people, well before. It was a hole that he knew was critical to fill.

A Vision for Knowledge

Long before he even opened the book store, Hakim was setting up tables at festivals and selling black history books out of the back of his car. Blake said his mission was to educate everybody. Blacks were still de facto second-class citizens at the time. What Hakim had learned and needed to share with the vigor of the recently awakened was that beyond even the struggles of the burgeoning civil rights movement, blacks had been an integral part of developing American culture, including politics, science, and education.

He had found a way to see a whole America that was the result of contributions from all quarters of culture and he needed to help people see how critical blacks were in that picture.

When he finally was able to open Hakim’s Book Store, he learned that derision also was colorblind. Yvonne said there was a sense that he was preaching to the converted. Socially conscious people already had a sense of black history and people who weren’t socially conscious didn’t read books like the ones he sold. In the earliest years, Hakim’s Book Store ran almost exclusively on belief.

“I used to go to the bookstore as a little girl, and I would hear people saying, ‘Why is Mr. Hakim selling those books? Nobody’s going to be buying books,’” Blake said.

But as the 1960s rolled on, people bought and people learned. Change was in the air and knowledge was the fuel. Hakim was more than a knowledge broker, though. He was a curator, an author, and a publisher of books he thought were too important to leave to the wiles of traditional publishing.

When Hakim died in 1997, there was a real concern that the landmark would die with him. Hakim’s was as much a passion project as it was a functional business, but people worried the passion died with the founder.

A New Generation

For her part, Blake wasn’t interested in the bookstore. She grew up in a slightly different America than her father. She went to integrated schools in Philadelphia and had friends of all races. It wasn’t until she got a little older that the importance of her father’s work was made clear to her. Like her father, Blake didn’t get the full importance of things, like her ancestors not being able to vote, until she was a little older.

Related: Déjà Vu Fun in Rediscovery of Now Heirloom Bookstore

She helped at the book shop occasionally but didn’t envision taking it over until her father’s death. After that, it became clear that either she took it over or it closed forever. Once Hakim and his family understood that he was at the end, Blake promised that she would keep the store open as long as she could. She and the rest of the family would pitch in to extend his legacy.

I’ve gotten so many comments from people that I knew. “Your father my father started prison mail order. He started shipping books to prison.” And we have met people who said, “Oh, your father sent me my first books.” People that are still here in Philadelphia, young people that got in trouble, went to jail. I’ve had people say, your father sent books to my son or my grandson, and he wouldn’t take any money. So these are all things I really learned after my father passed away.

— Yvonne Blake

The nuts and bolts of running a bookstore didn’t come easily. Blake had a “real” job with a regular paycheck and benefits and for years kept the store afloat out of her own pocket. Family members and friends took turns behind the counter, but none were in a position to give up their day jobs, especially since the shop struggled financially.

Blake rode the ups and downs for the 15 years between her father’s death and her retirement in 2013. Some people travel, others take up fishing, and Yvonne Blake decided to spend her retirement putting Hakim’s Book Shop on solvent footing.

There is some debate over whether Hakin’s is the oldest continuously operating black bookstore in the country, but there is no debate that it is one of the oldest. In Philadelphia, there’s also little question it is one of the most important.

Continuing a Legacy

In the wake of Hakim’s death, hundreds of people told Blake that he had sold (or just as often gave) them their first book on black history. He was in the business of opening eyes and challenging intellects. We all have books that have changed our lives, and many of us can remember who gave or recommended them to us. How much more powerful is that feeling when it is a relative stranger who just wants our lives to be more complete?

That was well and good for Blake, who accepted her father’s mantle, but she also was her own person. Her father took the secret of how to keep the bookstore funded to his grave, so she had to find her own way. One of her first steps was to take a continuing ed course on how to run a business.

The course was helpful, especially in helping Blake get ahold of accounting services, but no one in the book store industry had a course on what to do about Amazon, and by 2015, it looked as if Blake would have to close Hakim’s Book Shop. Sometimes, though, the admission that you’re struggling is all that’s needed to get the help you need.

At the mere suggestion that Philadelphia might lose its iconic bookstore, the community rose up in support. In addition to cultivating black history literacy in his own sphere, Hakim had a practice of sending books to incarcerated men free of charge. Suddenly, people who Hakim had helped were finding their way to the bookstore to support his legacy. There was news coverage highlighting the store’s place in the cultural history of Philadelphia that stirred up sentiment.

Meanwhile, Blake started getting help from younger people who wanted to volunteer. They helped her establish a website and a social media presence.

“I met the gentleman that now volunteers here young gentleman by the name of Brother Chris, and he’s like half my age, and he was just almost like a blessing that he was sent here, because I was getting weary and I didn’t know exactly what to do,” she said.

With Chris’ help, she was able to put together more targeted marketing.

Community Aid and Support

When George Floyd was murdered in 2020, Blake said that people sought knowledge and solace in the titles that were hard to get outside of a niche bookstore. It was the moment in history Hakim’s was founded for.

“It was like George Floyd got killed. They put it on TV and then all of a sudden everybody wanted to read a book. It’s really crazy,” Blake said. “They found online we have a great selection of children’s books that are specifically targeted. Not just African American children, but they have pictures of African American children. Like I read Dick and Jane in elementary school, and you didn’t see yourself in books. And that’s so important. I’m just trying to honor my father’s memory.”

A group recently petitioned to have Hakim’s Book Store added to the city’s register of historic places. A decision is expected in the fall, but in the meanwhile, Blake is grateful for the support the store has received and proud of the support it has lent the community as we enter the next chapter of race relations in America.

She did retire nearly a decade ago and hopes to eventually retire again, once the store’s future is secured.

“My hope is that my granddaughter, who’s going into her sophomore year at college, she works here in the summer sometimes, and she helps me out when needed, would be the likely one [to take over].”