At some point early in our lives, most people are told to be careful not to damage a book’s spine or to

“Look at that cover!” It is at that precise moment, these young readers are introduced, by their a teacher, librarian, or bookseller, to the idea that the parts of the book have their own names. Typically, people learn what to call the spine, the cover and the pages and then, for the rest of their lives, are satisfied with their knowledge of book terminology. That is fair, because let’s be honest, a lot of people never pick up another book after they graduate from school and not doing so does not impact their lives one iota.

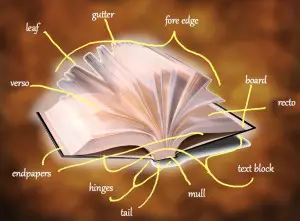

This is not true for the bibliophile, the lover of books, the man or woman who goes into an old musty bookshop just for the smell of aging paper. They live to absorb the knowledge in books and even the knowledge about books. They not only know every part of a book, but can explain the origins of the terms quarto, folio and describe exactly which burnishing tools 17th century Italian men preferred to fold them with. But short of a full-blown obsession with books, there are other valid reasons to learn the anatomy of a book. Maybe you make books. Maybe you repair them. Maybe you have inherited your great-aunt’s book collection and need to describe its condition to put up for sale. Either way, for every part of a book, there is a name, which can be quickly learned during a quiet afternoon. And the best way to learn them is by dissecting the book piece by piece.

Your basic cover is that thing around the book that protects the part you want to read. It includes a lot of other parts, too, but for now let’s just distinguish between the cover and the dust jacket, which is that often glossy sheet of paper that covers the cover. And turn it around to the back and there is that pesky spine all the librarians were always so concerned about.

Too basic? Not a problem. Now, if you ripped off that cover at its hinges and held just the sheets of paper in your hand, that part we would call the textblock. If it was a hard cover book, you would have had to tear through two large sheets of paper that attached both to the cover and the textblock on either end, which we call the endpapers. The half attached to the cover is called the pastedown endpaper while the part that hangs loosely with the textblock is your loose endpaper. These papers are not part of your textblock, so please throw them in the wastepaper basket.

Look at the pages on the opposite long edge where they are not bound. That is the fore edge. Set the textblock on the table on the back of the textblock, the part that meets the spine. Now, open it up, as if to read it. That part of the open book where the pages meet is the gutter.

Each single piece of paper from the spine out is a leaf. Having disposed of the endpapers, you may have revealed the blank sheets of paper underneath, which are called the flyleaf. If you are dealing with a hardcover book, the leaves may be formed from sheets of paper that have been folded in half and stitched together in groups. These groups are called signatures or rarely, gatherings. Sometimes a super or a mull, a meshed fabric, is glued around the signatures where they are gathered to hold them together. The mull flaps are attached to the inside of the cover.

Okay, let’s rip that stitching free! Now hold in your hand a single leaf. The side of the leaf that is read first, that faces up when the book is set on the table with the cover up, is called the recto. The other side we call the verso. Now that the text block has been dismantled you can use each page to create a paper airplane, crumple up or just stomp on them for the sake of being destructive.

Alright, moving forward! Looking at the cover again, on the spine, there is an obvious top, which we call head and a bottom, which is called the tail. Some hard covers may have raised bands along the spine. The places where the cover has been bent are called the joints. If we dissect the interior of the spine carefully in between its joints, we may find a headband, a small bit of board that is nestled in at the top. A tailband can be found at the bottom. Along the length of the interior may be a liner where the cover would have been attached to the mull, which we already destroyed. The cover itself consists of a board and may even a bit of fabric or paper wrapped around that, which we call the cover material. Throw the rest into the bathtub and we are done dissecting a book and ready to learn about book repair.

Carrie Bailey is an information professional who studied at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand and now lives in Raleigh, North Carolina.