Mystery books excite the reader; but book mysteries can be fun too. This week I came across a book about which I knew almost nothing, and so I set about discovering what I had. The book is “Poems,” by Owen Meredith. The inscription in it reads “Merry Christmas ’87,” and the worn, gilt-embossed padded-leather binding indicates the implied century is not our most recent. Normally, a few clicks on the internet tell me what I need to know about a book’s provenance; this time I could find out nothing about my particular edition. Really, is there anything more beguiling than a dead end?

Most old books are worthless. That’s a sad fact, but true. Most old books are worn out, their pages are torn or fragile, their spines are brittle and cracked, their covers are jacketless and plain. And they contain material that is dated, useless and obscure. As hard as it is to dump them, they need to be, let’s say, euthanized. They need to be culled from a bookshop because they clog up the shelves, litter the floor and positively, absolutely won’t ever sell. Customers bring me old books every day, books they have been keeping for 60 years, since their parents passed them down. They assume they must be worthwhile since, after all, they were printed, right? But, mostly I return these books to the customer, explaining that, old as they are, I just can’t sell them. Something about Owen Meredith’s “Poems” though, wouldn’t let me give up the hunt.

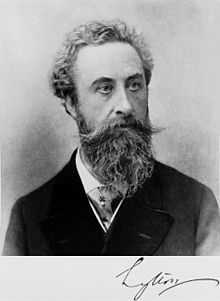

Owen Meredith was the pen name for a renowned diplomat and Lord of the British Empire, Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton, who from 1849 until he died in 1890 was in constant motion in the foreign service. He served in Washington, D.C., Paris, Madrid, Lisbon, the Hague, Belgrade, Constantinople, Vienna, St. Petersburg and India, the latter as governor general and viceroy. His career was a marked success, with two bothersome exceptions: the Indian famine of 1876 that claimed 6-10 million victims, and a futile war in Afghanistan that the Brits won, to their lasting regret. In any case, through his long career, the Earl was publishing highly-stylized, romantic and extremely popular poetry under his bland, inoffensive pseudonym. I say popular because his story poem “Lucile,” his masterwork, appears to have remained in print for some 78 years before slipping away in 1938.

There is plenty of information available about Owen Meredith, and “Lucile” is also well known. Oscar Wilde dedicated “Lady Windermere’s Fan” to Owen Meredith. At any one time you can find any number of copies available on the resale and auction market. But I could find no examples of my edition, which includes “Lucile,” along with most of Meredith’s other published works. After my first fruitless searches, I started to get creative. I searched using phrases from some of the lesser known poems; I searched using proper names from some of the poems; I searched for information about padded leather bindings, and their publishers. Finally I made a breakthrough; my edition was published in a binding style known as the Seal Russia Edition. When I searched for “Seal Russia Owen Meredith,” I found the mother lode of Owen Meredith arcana – a website known as the “Lucile Project,” the life’s work of Sid Huttner at the University of Iowa.

As a book collector, Sid Huttner is a specialist. He specializes in one book: “Lucile.” He started collecting “Lucile” in 1984 and has been acquiring copies of that book, and information about its publication history ever since. In one way, he has found an ideal subject to collect – something no one else wants. He says when he finds an interesting copy of “Lucile” on Ebay, he’s almost always the only one bidding. Because he is the only collector with much interest in Owen Meredith, the books rarely sell for more than $5 or $10. And he finds lots of interesting copies of “Lucile.” On average he finds 75 new “Luciles” every year. The last I heard, Huttner had found upwards of 1,200 different editions of this long lost favorite, published by more than 100 different publishers, all between 1860 and 1938. If there is any question about the popularity of “Lucile,” think what it means for a work to be issued in so many editions. There are folios, boxed editions, illustrated editions, quartos, octavos, cloth and leathers of all types, small books with just “Lucile,” and collected works like mine. Imagine if “Love Story” were still popular today, and for another 30 years, and had been written by Henry Kissinger.

My search, finally, led me to something that all book collectors must fantasize about. Huttner has a webpage for each edition, identifying the publishing details and each book’s availability. I found the page for the Seal Russia Edition, and this is what I found: “No copies have been reported.” Was it possible that I had the only copy of a book that nobody wanted, except, Sid Huttner?

I emailed Huttner, and he quickly replied with disheartening news. Even he didn’t want it. It turns out that in my round about searching, I had found an old out-of-date cached page, and in the intervening time, the only person on earth who might want my book, had found another copy. Mine is, I take it, the second known copy of the Seal Russia Edition, 1886, of Owen Meredith’s “Poems”, and, as such, just another old book that I need to cull. Unless (and this is my big new idea) I become the world’s second Owen Meredith collector, if only to give Huttner some company. I would love to see his face when, for the first time, he sees “Outbid” pop up beside his $2.31 Ebay bid on the next “Lucile!”

The neatest thing for me about the Lucile Project is that it helped me date books (doing a juveniles cataloging project) through the publisher information – the address one was at for just a year or two would be a sufficient stand-in for date information given that many juveniles at the turn of the century had no copyright/publication date (and OCLC, if it had anything at all, was often very vague (19??) or just plain wrong (giving the year the title first appeared, decades before this edition, etc.)).