When ever I’d ask my father what he was doing, he’d answer, ‘writing How to Win Friends and Influence People.’ As a kid, I’d no concept of what that meant–the entire idea of winning friends was beyond me–didn’t they just show up? And how did you ‘win’ them anyway? Like at a carnival game–shoot enough ducks and you win a stuffed friend? And the word ‘influence’ was not in my child’s vocabulary. This phrase and several others–when I’d be hungry and say so–‘eat some salt and you’ll get dry’ and if asked the same question about activities my father was engaged in–‘playing Tiddelly Winks with man hole covers’ became something rote in my mind, not real. It was a surprise when I found that a kid’s game actually existed named Tiddly Winks. And an even greater shock when I grew enough to realize someone really wrote a book with that dopey title!

I didn’t investigate the content. I was bemused that my dad’s only choice for writing would be that book. Where he came up with it, I’ll never know, I didn’t ask when I should have. For a fact he never read it. I doubt he could have explained a single thing about the idea of winning friends, and yet this book was his automatic response to any question. Odd. When he was deep inside himself with Alzheimer’s, I came across a beat up old copy at a library sale, and on impulse bought it, laying it next to his bed. I wasn’t delusional enough to think he’d be able to understand what was in it, or even try to read, by that time he was barely verbal. I guess it was for me–a reminder of who my dad once was, who he may still be under the coated brain waves. I’d have given pretty much anything for him to be able to answer that silly way again.

I knew it was over when the usual greeting each morning ended. I would see my father, and say, Hi, Dad’. and he’d respond with a great sigh, and mock disgust, Hell-oo Di-ane. In broken syllables. It was as rote as his old sayings. It was familiar enough that this greeting remained long after much else he understood left him behind. The day he didn’t answer, was the day I lost my father. Not the months or perhaps years later, but at that moment.

Why does it seem that dementia tends to rob the very people who have the most coherent thought process, a logical sound brain? I can’t think of much that is more terrifying than watching a person whose common sense is slowly losing traction, and that person understanding it’s happening on some level, but impotent to halt the nonsensical workings of their brain. My dad never knew he had the disease. We chose not to inform him, against all the books advice. What function would it have served? By the time the so called senior specialist declared that my father had the disease, he was fairly far gone, and the pathetic meds for it only slowed it down for a more torturous lengthy process. (The way my mother was told my father was stricken, was with a flippant, yes, he has Alzheimer’s. That was it. After tests and tests, she had to ask! And this is all the damn doctor said.)

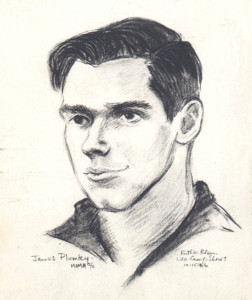

My mother liked to claim my father’s brain was always working. He could come up with all sorts of things just by being. He was no educated man–he dropped out of high school a month before graduation because he was wrongly accused of throwing an eraser. He later worked hard to earn his GED. He joined the Navy at 17 to fight in WWII. He won my mother through letters during his stint. He worked as a maintenance mechanic–meaning, he fixed bakery equipment. He became the plant manager at a local pretzel factory and designed some of their machines with another thinking man at the factory. He was called in at night for emergencies, he was a miracle worker in his craft. He was valued, but not rewarded. He was a quiet man who would discuss his work at dinner in detail, explaining about the main extruder breaking down and not twisting the pretzels properly etc. I would tune out about 2 minutes into the recitation, because that’s the only conversation we ever had at our prompt 5:30 dinner. And it drove me to distraction. I didn’t understand a word he uttered, nor did my mother, or brother. But we never interrupted or bugged him, he had to let off steam, and he did. Then off to the model railroad club in later years, or in the living room for a Phillies game.

He fixed everything that ever broke in our house, electrical, plumbing, the TV when they had tubes, same as the radio, the car, when cars could be fixed. When he visited me in my NY apartment, he was uncomfortable unless he was working on fixing something. I never saw him so frustrated when he couldn’t fix a jukebox left in our apartment by the last tenant–he didn’t have the parts. He could not just sit on his hands and hold a conversation. What the hell good was that when a light-switch was broken? I would call him if panicked about some electrical thing or another in the apartment, afraid of a fire, or some sort of disaster. He’d sigh, tell me why I was a nitwit (he never ever used derogative terms, I felt like one after he explained things, lol) and I’d feel safe as though he were there.

He calmed fears. When diagnosed with cancer, he was comforting me. He beat the cancer and lost the war to dementia I am convinced was brought on by a life threatening incident in the ICU after his surgery. He was not the same man when released from the hospital. It was slight, written off as post surgery behavior, but he was altered, as if another slightly less congenial personality had taken over. As time passed, he began forgetting things–ordinary enough for anyone 69, but it progressed to the point where he no longer could fix anything, calmly explain away fears, understand. That’s when I moved down to help a mother who had shouldered his care alone. A doctor had put him on meds that were clearly marked right on the bottle not to be given to dementia patients — he was acting out–angry, hallucinating. He actually hit me in the stomach, thinking I was doing god knows what. I had to chase him after he left the house, fearful something may happen to him. Another time I was awakened by repeated ringing of the phone. I had a sick feeling in my stomach and looked out my window to see him hurrying down the street dressed only in his shorts and a sweatshirt twisted around his head. People all over the neighborhood were calling to alert me. I found humor then, but am hard put to find it now. The degradation this disease causes its victims is overwhelming. A man who could be depended on to think problems through logically and clearly wasn’t able to understand how to put his clothes on, or where he was.

We had hospice come in when I finally realized we could have had help from them all along–Alzheimer’s is always fatal, and my father was dying each day. The nurse was wonderful and thought my father had many months left, but I knew, I knew he was dying now, right now. Three days later, as I was scooping out ice cream, my father began that awful sound that the dying make. In the middle of a mundane action, opening the refrigerator, pulling out ice cream, my father’s life force was draining away. In the middle of the afternoon. In the dining room that was converted to his bedroom with Pennsylvania Railroad memorabilia all around, the person who spent years thinking, creating, fixing, and writing ‘How to Win Friend’s and Influence People’ physically died.

I started writing this as a humorous piece about the book, and realized it was really about my father. It’s so hard to remember the person before the disease sometimes, that it’s essential I try to every opportunity I get. To see him in my mind’s eye as a victim of disease, is to negate his true self. The thinking man, the one who created for me out of practically nothing, tools for my jewelry trade before anyone had ever thought to make little stamps for polymer clay. They weren’t pretty, but they worked. That’s just who he was. A man who was unlikely to write a book, for certain, but one whose best saying was, “you can do anything you put your mind to”. That his mind is what betrayed him, is the most difficult part of his death. But shouldn’t define his life. And it’s time I stop letting it.