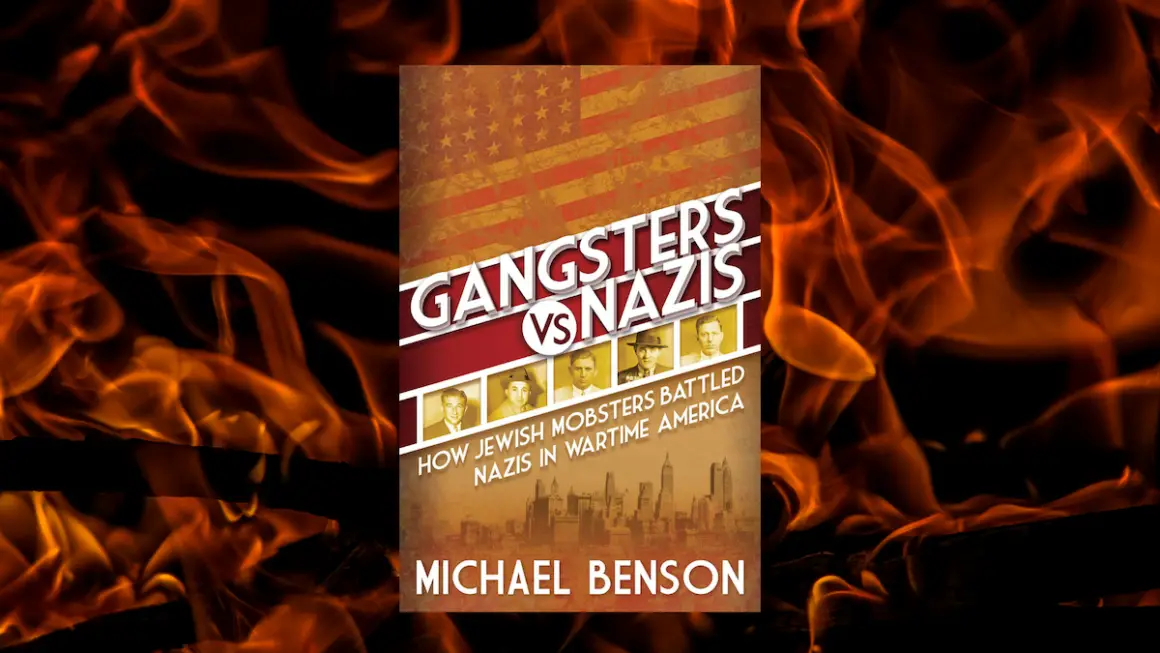

How the mob saved America from 1930s fascism in Gangsters Versus Nazis

The Depression-Era violence perpetrated against U.S. citizens by the government, from strike-busting by National Guard troops to General Douglas McArthur gassing WWI veterans on the Washington Mall, is shocking even by today’s standards. That’s to say nothing of the Japanese internment camps, the mass starvation, the uptick in race violence all across the South, and the rise of the German American Bund.

Related: A Talking Cat Shares the Meaning of Life and Books!

Anything more than a cursory study of the Depression will leave you in awe that we didn’t descend into civil war.

The open attempt by Nazis to organize an army across America, as they had done in 1920s Germany, succeeded in making tens of thousands of citizens openly pro-fascist. As it turned out, Jewish gangsters were among the American heroes who helped stem the tide of 1930s fascism. Gangsters Versus Nazis, by Michael Benson (Citadel Press, 2022) reveals a national, coordinated effort to squash the Nazi movement.

The story, like the era, is so morally ambiguous that it leaves those of us who pity the women, addicts, terrified small business owners, and others whom the mob preyed upon wondering who will fight the Nazis today.

In pop culture, Nazis are the perfect villains, easy targets for violent, Tarantino-esque wish fulfillment. Besides being always and completely immoral, they’re an incipient cultural cancer that will accept nothing short of total victory. In regular culture, many of us struggle day to day with the disconnect between supporting free speech and accepting its implications.

That was not the case in fractious, Depression-Era America. As Benson points out, there were common and open calls for replacing democracy with fascism as what was left of the fragile middle class wondered aloud whether everyone was really qualified to vote.

Hitler’s attempted consolidation of Europe was evidence to many that one strong, plain-spoken leader could accomplish more than a bunch of bickering politicians.

What separated the Jews (besides garden variety racism) were letters from the old country. Talks about neighbors disappearing weren’t uncommon. Long before Kristallnacht, they had a sense of how bad it was for Jews under the Nazis.

The Real Conspiracy

Enter Nathan Perlman, former N.Y. Special Deputy Attorney General, assemblyman, and congressman, future judge. Perlman watched the rise of the German American Bund and other Nazi organizations in terror and disgust. He knew what was happening in Europe, how the Nazis had used their freedom of speech to gain power and then rescinded rights for non-Nazis.

He watched the tide rise with no legal way to stop it. Then he picked up the phone and called Meyer Lansky, a man who needs no introduction to mob enthusiasts. If you don’t know the name, suffice it to say that most of the modern picture of how organized crime works came out of his head. In his elucidation of the mob’s inner workings, Benson provides a thumbnail sketch sufficient to bring in the uninitiated without boring those of us who read books about the mob.

History hates nuance and thus keeps many dirty secrets.

— Michael Benson in Gangsters Versus Nazis

He also paints the entire cast of toughs and killers with a sympathetic-enough portrait to give the reader context without undermining their crimes. If he strays from objective description at all, it’s in the title, which could easily have been Gangsters Mercilessly Beat Nazis Into Submission. There rarely, if at all, were versus-level confrontations.

Perlman also recruited rabbis as a buffer. Although he had no compunction about actively violating Nazi First Amendment Rights, he wanted to make sure the mob stayed on the right side of the Biblical prohibition against murder. The incongruity throughout involves the gangsters worrying more about their mothers discovering how they earn their living than they were about being arrested.

Family ties are the reason that gangsters get a pass that serial killers don’t, at least in non-fiction anyway. When discussing Perlman’s decision to align with the mob, promising protection as long as no one is murdered, Benson observed mobsters made the perfect allies: “They hurt and killed people for a living and didn’t much care about the law.”

What’s a disorderly conduct charge to a professional assassin, especially when the fix is in among the judiciary? As long as no one got killed, sentences for beating Nazis consisted of a scolding by the presiding judge.

A Cinematic Story

Because the book relies so heavily on brief biographical sketches, Benson moves from hard facts to musical prose to keep the story from getting bogged down in dates and descriptions. He evokes classic noir both in the prose style and by relying on stage direction (cut to, fade in). These are deployed as kind of reverse speedbumps, letting you know that the action is about to ramp up.

While there is some blood and gore, the descriptions aren’t gratuitous. Plus, at the risk of introducing a spoiler, the only people who get really hurt are Nazis. And there were a lot of them.

Benson takes us to most major American cities and not a few minor ones for a look into how well and easily Americans were swayed by or at least receptive to the Nazi menace. This is where the work shines as a history.

Read Other Bookshop Blog Book Reviews Here

It’s in no way novel to observe that many of the things that hate-mongers say online would get them punched in public. Gangsters Versus Nazis is about a time when that actually happened.

The end of many stories is the same: Perlman calls a local gangster and a local rabbi and sics them on the Nazis. But there are spies and intrigue. There are also plenty of Americans who are happy to be pro-Nazi until the punching starts, and that is the most revelatory, terrifying aspect of this work.

It is only barely an oversimplification to say that early 1930s Americans were for (or at least ambivalent about) Nazis until punching them was an option. The gangsters became catalysts, showing the country, neighborhood by neighborhood, that some people only respond to violence.

After that, punching Nazis was in vogue, and shop workers and bank managers stood elbow to elbow with thumb-breakers for the chance to crack Nazi skulls. In many instances, “civilian” participation was nondenominational.

The Bigger Picture

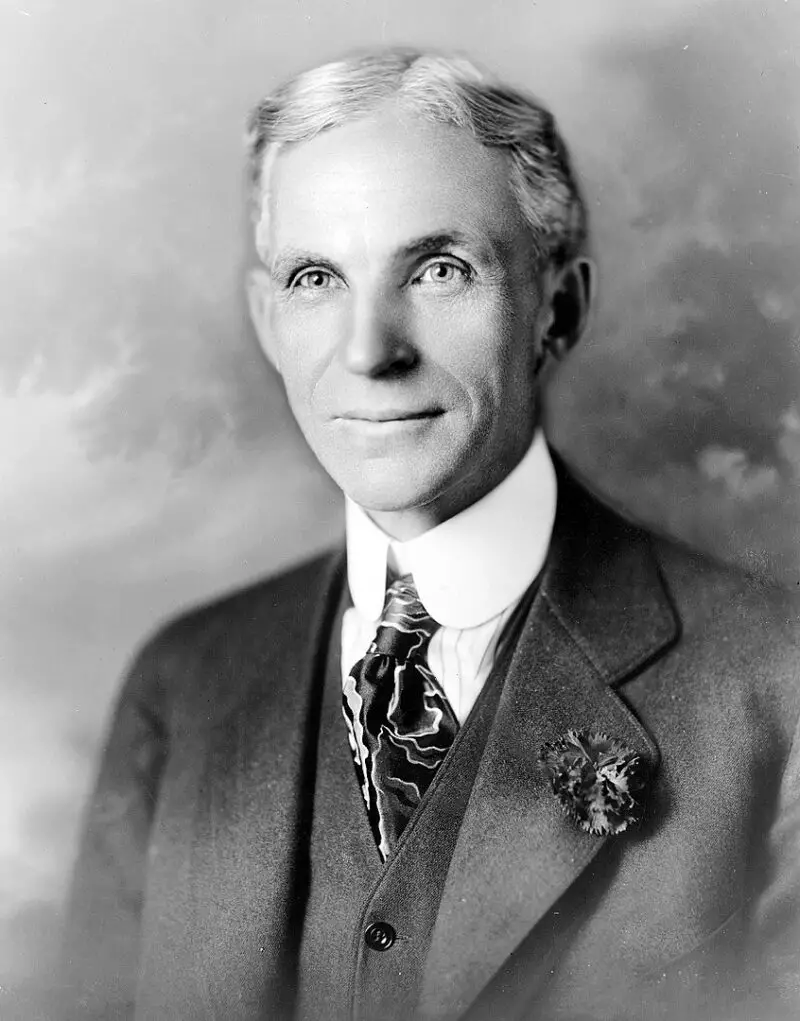

In painting the anti-Jewish sentiment that pervaded American culture, Benson doesn’t hedge, calling out antisemites, like Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh, among others. His discussion about an American past fraught with heroes being villainous and killers demonstrating virtue calls to mind the current controversy about whether and how to view American history.

“History hates nuance and thus keeps many dirty secrets,” he writes. In the digital age, another way to say it is, “Don’t Google your heroes.”

In the end, as seems to always be the case with demagogues, the Nazi leaders turned out to be liars, charlatans, and thieves. Weakened by the gangster onslaught, the Nazis retreated back to their holes to wait for the internet to be invented.

Still, the book haunts me. I like a good gangster story as much as the next guy, but it is hard to endorse the idea that a judge would use religious and criminal leaders to strip a political minority of their First Amendment Rights.

“Endorse” isn’t the word I want.

“Root for” does the trick.

I wonder what it says about me, about us, that I finished this book more worried that we didn’t have gangsters to root for than about how enthusiastically I cheered what would be horrifying moral lapses if Nazis weren’t the targets.

I know there’s a material difference, but only in retrospect. As much fun and as enlightening as Gangsters Versus Nazis is, it raised for me troubling questions about my place in history and my view of it. Beyond the juicy revelations (and there are a ton) and the satisfying descriptions of brass knuckles on Nazi noses, that is what makes this book such a compelling work.

Tony Russo is a journalist and author of “Dragged Into the Light: Truthers, Reptilians, Super Soldiers, and Death Inside an Online Cult.” You can find more of his writing here.