It is March 1970, and American journalist Albert Parry writes a fascinating article in The New York Times about “the new and remarkably viable underground press” known as Samizdat – “self-publishing.”

He writes:

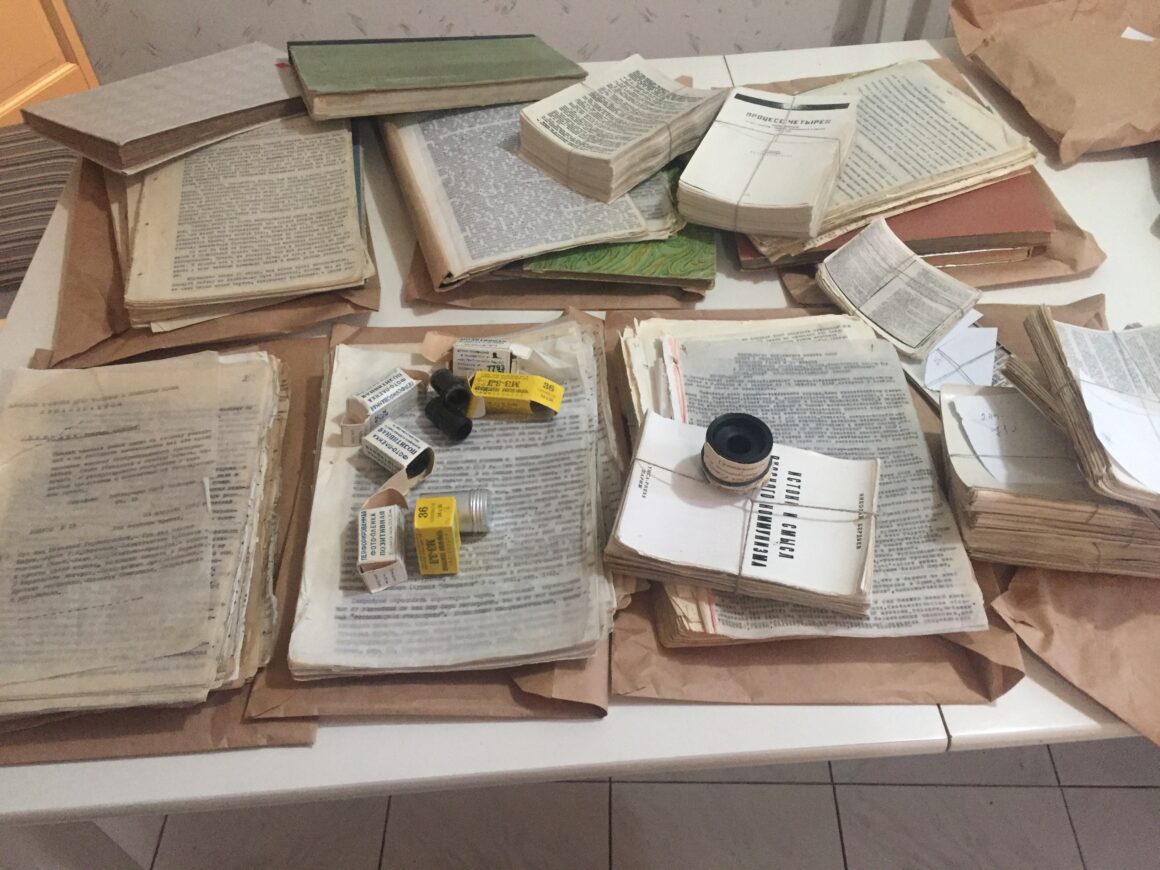

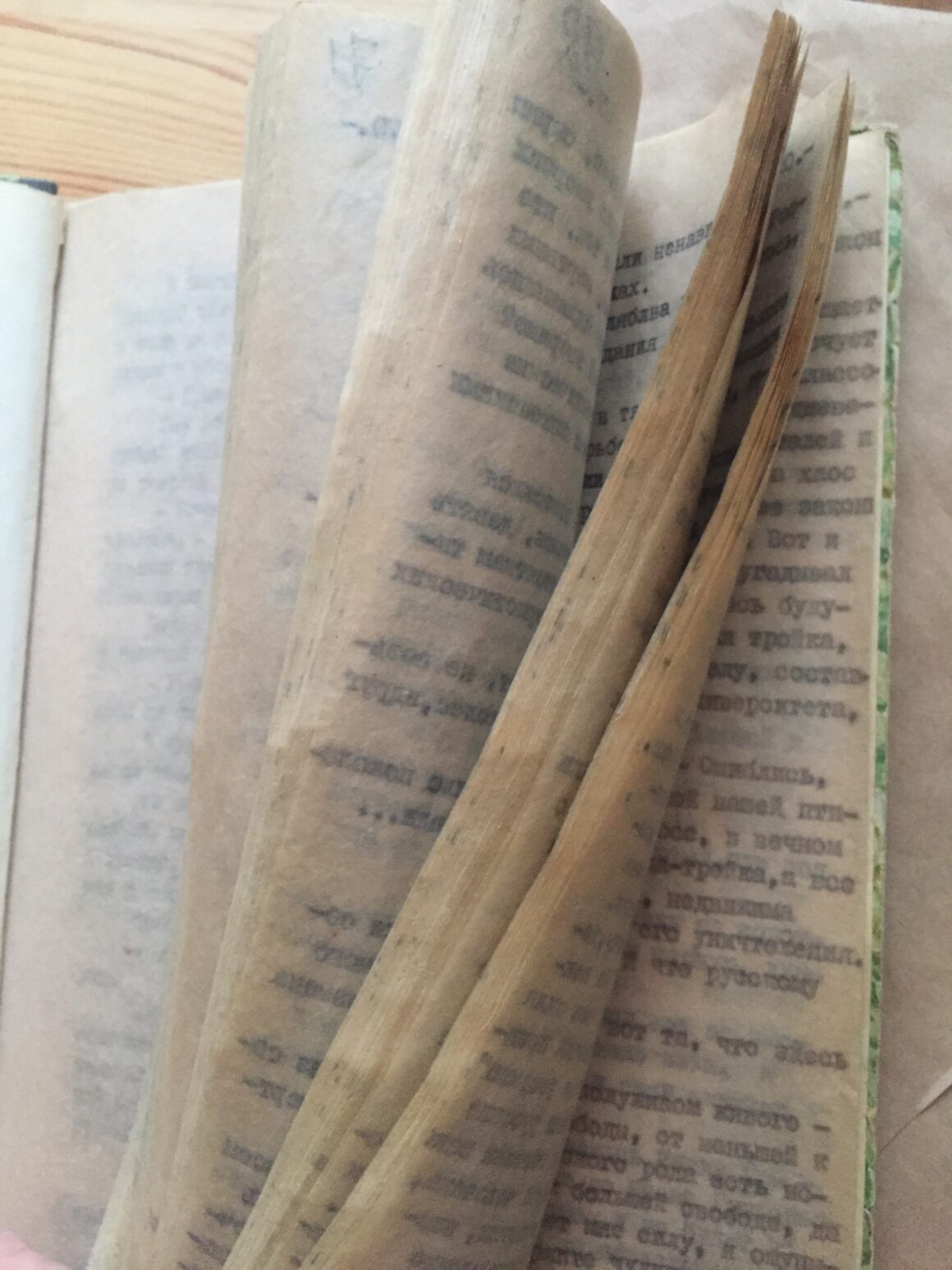

Unlike the underground of Czarist times, today’s samizdat has no printing presses (with rare exceptions): The K.G.B., the secret police, is too efficient. It is the typewriter, each page produced with four to eight carbon copies, that does the job. By the thousands and tens of thousands of frail, smudged onionskin sheets, samizdat spreads across the land a mass of protests and petitions, secret court minutes, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s banned novels, George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and “1984,” Nicholas Berdyayev’s philosophical essays, documents of the Czech Spring, all sorts of sharp political discourses and angry poetry.

Albert Parry, March 1970, The New York Times

And how did the West know of the nebulous Samizdat during the 1970s? For, as Parry wrote, the KGB would quickly put a stop to anyone trying to report on it from the outside.

In Parry’s case, he himself had recently traveled through Europe and attended what must have been an incredible occasion:

Munich’s Institute for the Study of the U.S.S.R. ran in London a three‐day symposium, entirely in Russian, at which recent Soviet defectors, mostly writers (headed by Anatoly Kuznetsov and Arkady Belinkov), but also musicians, film directors and professors now living in England, Germany, France and the United States, discussed the problem of Soviet censorship and the ways of eluding it: I was invited to attend and listen. In London, at the conference and in numerous private interviews, and later also in Munich, Frankfurt, Paris, Zagreb, Belgrade and New York, I met these and other experts on samizdat. Files and piles of the most diverse underground publications were placed before me. Facts, rumors, personal experiences, ideologies were offered by old Western hands in Kremlinology and the latest Russian perebezhchiki (“crossers‐over,” as defectors call themselves).

The Chronicle: a Samizdat journal you can read today

Parry writes of how one samizdat journal, The Chronicle, which had been operating for two years at the time (astonishing, in the circumstances), moved its operations from place to place, likely between various Soviet scientific centers, and new editors replaced those who were arrested.

Actually, you can read much of The Chronicle as it has been translated into English and published here. This journal operated for 15 years, during which time more than half of the managing editors were arrested and sent into exile.

He tells of how samizdat operations depend on mutual trust, the geometric nature of the distribution networks, and of the ordinary people laboring over carbon paper or typewriters into the small hours of the morning.

One of The Chronicle’s editors, Pyotr Yakir, was arrested by the KGB in June 1972. His wife also was arrested, and their apartment was searched.

Following this, a letter was sent from an anonymous group of Russian citizens. A quote from this letter:

The arrest of Yakir, a man who consciously placed himself at the spearhead of the struggle, does not mean that ‘all is lost’, that the authorities have achieved a victory with their policy…The arrest of Yakir is neither a beginning nor an end: it is an important landmark…to preserve people and to preserve samizdat, to preserve and strengthen the movement for democratization – that is the chief aim today, that is the best answer to the arrest of Yakir…

The Chronicle, No. 26, 5 July 1972.

The Dangers of the Written Word

Ekaterina Poleschuk recalls her father producing samizdat in their home:

My dad and his friends distributed samizdat that they probably got when it came from abroad. That’s how we read Bukovsky, Solonevich, and Voinovich’s Ivan Chonkin… Dad did the bookbinding. I often remember the smell of glue boiling on our stove. He would clamp the photocopied or printed pages, place glue on them and then after some time place them into the cover, which he also made. That’s how the samizdat book was produced.

Even Russian authors published overseas did not escape the KGB. Andrei Sinyavsky, for example, was arrested for having his stories and novellas (critical of Stalin) published abroad. A closed trial took place, and the proceedings were published by samizdat.

Ekaterina Aleeva, for Russia Beyond, reports that from the 1950s to the end of the 1980s, over 8,000 people were convicted under Article 70 of the Criminal Code, “On Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda. Also used to arrest writers and publishers was Article 190-1, “On The Distribution of Deliberately False Fabrications Defaming The Soviet Order.”

Today’s Samizdat

Censorship today takes a different form; dissenting authors may lose their jobs, be doxed, or have their own or their families’ safety threatened. This has certainly happened to friends of mine. Digital formats, I believe, make it even more difficult to produce secret documents.

What do you think will be the new form of samizdat in our era?