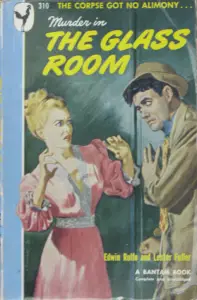

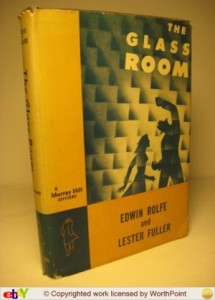

The Glass Room Edwin Rolfe and Lester Fuller 1946

“In 1946 the phrase first appeared in the murder mystery novel Murder in the Glass Room (by Edwin Rolfe and Lester Fuller) as “you can never tell a book by its cover.” Wow, that fact, I just found, may tip the book onto the list! We’ll see.

Whenever I’d pass a particular spot on one of the myriads of bookcases, I’d see the spine of The Glass Room and remember that I had really liked it. Finally, after thinking about it again and again, I decided to reread. I thought maybe I was leaving out a book that should have made the Best 100 list, if I kept thinking how great it was. So I did–reread it. And now I can’t decide. Yes, it was pretty good, but I’m not sure why. The plot wasn’t much to speak of, and the protagonist isn’t lily white, the circumstances are a bit far fetched, and I probably knew the murderer pretty quickly the first time around, only because I’d chose the least likely individual, and that’s who usually done it, back then. This time I didn’t bother trying. I wasn’t surprised, but I bet many readers were, and maybe still would be.

I’ll explain the reasons why it shouldn’t be on the list first. The action takes place all around L. A. in 1945–even though published in 46, it took time from written word to printed page, and while he wrote the book, the war was still on–at least the Pacific part of it. And that’s a big part of the ambiance and setting, the ongoing war. But what’s implausible to me, is Phil Norris, wanted for murder of his soon to be ex-wife,

Edna, could elude the police for the length of time he does in the plot. He moves from one part of the city to another, on foot mostly, sometimes aided by a gorgeous gal, whom he just met and who has declared her never ending love for him. One scene especially comes to mind as unlikely–he’s at the Hollywood Bowl with the new paramour, Shelley Callaghan, and they are the only people within the vast space, high up where he can see if anyone should enter or exit. I have no idea if this is the first time the Bowl was used in this fashion in print, but it sure has been overused on TV. I swear, if shooting in LA, every detective show has at least one episode where the protagonist is chasing the bad guy up the long stairs or is shot at by the bad guy who is already up the long stairs. In this book, he and Shelley are exchanging info, and other things, when the cops do arrive, and he manages to escape–she pretends she wasn’t with him, or know him, that she just happened to be there. I find that a bit hard to swallow, but, one must suspend disbelief when reading such things, I suppose. Another irritating aspect–a female friend had found Phil when he was just a teenager, and took care of him, like a big sister. There is some discussion about if she were only 15 years younger, or he older, they would have been great together. I understand that older women were not OK then, even though a male in his 50s could be with a barely legal girl. Hell, an older woman still isn’t accepted. I never tire of the looks on people’s faces when I state my husband’s age and the difference between his and mine. Invariably the men are stunned. The women are delighted. And I just don’t get it. But my personal prejudices on this theme shouldn’t weigh on the quality of the work. I just thought I’d mention. Ha.

The character of Shelley is rather thin. There’s not much to her, the reader has no idea what makes her tick, which may have been a choice for the authors. I wasn’t happy with the way Phil and she get together so quickly, and by getting together, I mean have sex. It smacked of Mickey Spillane, although he hadn’t begun writing his hopping in bed books yet. I’m certain the really pulpy novels out there were chock full of sexual activity–after all some of them had titles like Bouncing Betty–she’s a mattress tester, Why Get Married, and She Couldn’t Be Good. But for a straight crime novel, their romance moved too fast.

Why should it be on the list? For some of the same reasons it’s weak. The sightseeing tour Phil leads the reader on is fascinating. You get a full picture of what that city was like in 45 from the point of view of a hard-boiled bookie. That’s what Phil is, in the beginning of the book, a self made man, with a luxury apartment, an ex-wife living in a mansion he paid for, and a slightly slimy partner. He wants his freedom from Edna, who turned from provocative alluring dream woman, to grasping, bitchy, lying fiend. She is a typical noir novel’s depiction of the opposite sex. Gorgeous, sexy, and nasty as hell. She deserves dying, as one character claims. Phil knows he’ll be the fall guy–he found her body, called in the crime, before he realized how his presence there would look. When he finds her date book, he decides to follow whatever she had penciled in

to do the next day, and he does it, eluding police the entire time-even after it’s clear he’s a made man. Scenes are set in Hollywood Hills, elite stores in downtown LA, the barrio, Venice Beach, the farmer’s market, the strip, and various other spots around town. The plot has levels to it–including a suspicious leader of a group supposedly campaigning for veteran rights but as Phil discovers when attending a meeting that the focus was more on blaming the Jews, and minorities, than helping vets. The language pulls no punches, unusual for that time frame. It is succinct and masculine. The book would have made a nice Noir film. Maybe it was! Once Hollywood got ahold of a story, they would re-write until nothing was left but the title, and even that might be changed. There are a good number of suspects, and a variety of reasons to kill Edna, and Phil checks out them all–from the bogus leader; to a member of the group; his partner; a little pain in the ass guy who wants money from Phil; Edna’s overly admiring dressmaker; a childhood girlfriend now a slutty drunk; eventually, even her father comes under scrutiny. The reader adds Rosa, Phil’s older friend; and Shelley, the mysterious woman who just happens to be a reporter working on a story about the veteran’s rights group.

Written in the first person, it owes much of its style to Hammett and Chandler, but then, what hard-boiled book doesn’t? After reviewing what I’ve written, I still can’t decide. I suppose I’ll have to look over the list, yet again, sigh, and see if there is a weaker entry, that needs to or deserves to be bumped for this one. I can’t imagine why I thought coming up with this list would be easy.