I’ve only tried to contact an author once. It was when I was in fifth grade, and I had been reading The Mysterious Benedict Society by Trenton Lee Stewart. I wrote him a letter full of shameless praise, signing it “Shelby, AKA Shelbell.” That’s a nickname I haven’t gone by for a decade now, but you know what? I thought I was going to die of happiness when he replied to my letter and I discovered he had signed his return letter to “Shelby, AKA Shelbell” by hand. Mr. Stewart knew and used my nickname. I was big stuff.

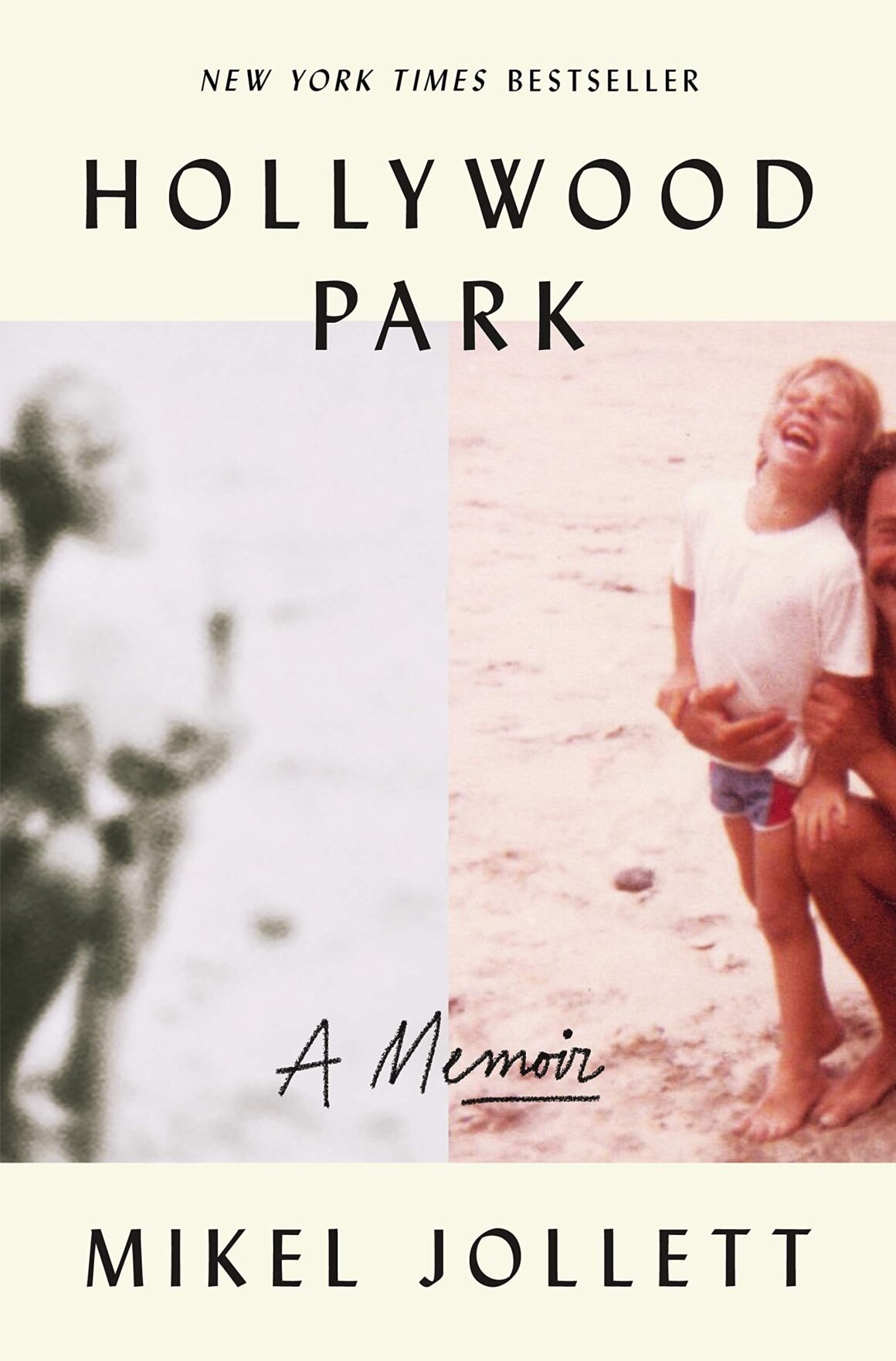

While I’ve enjoyed numerous books since then, there’s only one book that’s taken me back to that level of authorial devotion: Hollywood Park by Mikel Jollett. Jollett is a childhood survivor of Synanon, one of America’s most well-known cults. His memoir starts there and continues to follow him to adulthood and the creation of The Airborne Toxic Event, the band of which he’s currently the front man. By the time I reached the sections where he discusses the band and his more recent years, I was in awe of his prose and felt like I knew him—like I’ve known him all my life and should now be attending all the band’s shows.

When I finished Hollywood Park, I actually looked for ways to contact Jollett. I had been following him on Twitter since before the memoir was written, and when I saw that he didn’t have his DMs open to the public, I realized that I was acting a bit, well, stalkerish. I just want to tell him how much I loved his book, I told myself. That’s the magic of this memoir: Jollett opened himself up to the point that readers feel like they genuinely know him by the time they reach the last page (for some, to the point of wanting to offer him personal words of praise and admiration).

“We Were Never Young”

Those are the memoir’s opening words. Jollett begins at his earliest memories and does so through a unique, childlike voice. Writing from his perspective at the time, he even spells things how he heard them when he was young: “New Yoke” instead of “New York,” “moto-cycle” instead of motorcycle, etc. This voice continues to mature as he does, which was my first indicator of Jollett’s incredible literary talent.

Related: What Are Memoirs?

Even so, Jollett’s correct. It’s evident from the very beginning that he never really had the chance to be young—to be a typical kid with typical kid concerns. Synanon distorted his concept of what a family is, which he manages to portray so specifically that it feels like his memories of the cult happened yesterday: “Mom and her sister Pam, who is something called an aunt, and her brother Jon, who is something called an uncle (those are things that happen in “families”).” And so, this child who only knew the term “family” as something to be put in distant quotation marks was somehow meant to navigate the world. Lucky for us, Jollett takes us along for the ride.

“I Wonder if I’m Going to Grow up to Be One of Them”

This statement, made in the first half of the memoir, is what I think is the central theme of this book. However, I’m careful when applying “theme” or “tone” to memoirs because I know a real person has offered a real life for readers to peruse. Even so, Hollywood Park seems to be the result of Jollett looking his family and upbringing in the eye and asking, “What have you made me?” And, “Have I become like you?” Jollett creates clear links between the events he chose to include, with every detail impacting who he’s become today.

At the heart of these considerations are his parents. Even after escaping Synanon, his relationship with each parent is complicated. “Which will I grow up to be?,” young Mikel asks, “Because it seems like my choices are limited to being the one who leaves to use drugs or the one who stays home and cries about it.” His observations are painfully specific yet resonant for us all, no matter how good or bad we would deem our family situations. Isn’t it hard to look at where we come from and not wonder if our paths are already decided for us? Jollett gets to the heart of these concerns and where they led him.

“We Don’t Want to Be Understood”

One of my favorite aspects of this memoir was its fantastic vulnerability and astute look at the labels Jollett received throughout his life. His mother was a fan of psychology books and “figuring out” what exactly was wrong with everyone. This isn’t an uncommon occurrence, but it’s hard to articulate how it feels to be on the receiving end of this kind of attention, except for Jollett.

“We don’t want to play our part” was his teenage response to prescribed roles his mother’s books said members of “broken families” were meant to play. But that wasn’t all: “We don’t want to find ‘the peace of the forest,’ we’re not interested in ‘family time by the fire.’ We just want to be left alone with our music. Exactly misunderstood. Precisely unloveable.” That, I think, speaks for itself.

This Is Your Shameless Letter, Mr. Jollett.

When asked what he’d like readers to take away from Hollywood Park, Jollet replied, “I guess there are some fancy things I could say about emotional resonance, landscapes of the mind and the sob in the spine of the artist-reader (that’s how Nabokov put it) but any first-time author is lying who doesn’t simply say, I really hope people like my book.” After reading the memoir, I hope that “first-time” becomes second-, third-, and fourth-time because there will always be room on my bookshelves for anything he decides to write in the future.

If I tried to remove any passages from this book that didn’t ring true, there’d be no pages left. It’s a challenge, a privilege, and a pleasure. Yes, Mikel Jollett, I liked your book.