“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

Hannah Arendt (The Life of the Mind, 1978)

In fictional stories, as in real life, we know that events, inner struggles, and moral decisions can take people from the “dark side” to the “light.” Literature and the arts are filled with this phenomenon. One German film, The Lives of Others, features a book that pays tribute to the main character, who transitions from ingrained evil to goodness. To the jaded and pessimistic, this poignant transformation works like a balm to the heart.

But wait. Sometimes goodness is ambiguous, isn’t it? Does society set the rules, or is it in one’s character to decide, depending on the situation, what is the right thing to do? The same standard applies to being bad. Or certainly, “bad-ish.” Vice versa, to complicate the issue, circumstances can drive one from good to bad actions to survive in one’s world.

For example, a person educated and groomed for doing good against all odds—say Michael Corleone in Mario Puzo’s The Godfather (1969)—is forced by family honor to kill his father’s attempted murderers and is sent to Sicily to wait out any retaliatory vengeance. His fate remains undecided. When he loses his beautiful and innocent Sicilian wife, Apollonia, to a car bombing, Michael’s path veers into the violent one his father Don Corleone wished him to avoid. Good that runs to bad or ultimate evil is another story unto itself. The vagaries of what pushes someone in either direction are always in question. It can be a very fine line.

First, let’s take a look at the twists and turns of what being a good person means. And then, we’ll reverse course. Or end up somewhere in-between or beyond limits.

From Bad to Good

Les Miserables, by Victor Hugo (1862)

In 18th century France, Jean Valjean steals a loaf of bread to feed his hungry family and after his arrest becomes prisoner #24601. A convict at that time was forever branded a criminal by a piece of paper issued following his release. Valjean is given shelter by Bishop Myriel of Digne, who is described by Hugo as the personification of a good and pious man.

“There are men who toil at extracting gold; he toiled at the extraction of pity. Universal misery was his mine. The sadness which reigned everywhere was but an excuse for unfailing kindness. Love each other; he declared this to be complete, desired nothing further, and that was the whole of his philosophy.”

Valjean steals some of the church’s silverware. When the police arrest him and bring him back to the church, the Bishop says that he gave the silver to Valjean to start anew, plus he hands him two additional silver candlesticks. From this point forward, his soul infused with the Bishop’s admonition to be an honest man, Valjean vows to be good for the rest of his life and will be sorely tested in the days and years to come.

Later, Jean Valjean and his charge, Cosette, hide in a nunnery to escape pursuit by the relentless police Inspector Javert, whose goal remains to track down Valjean and return him to prison. The nuns have provided sanctuary for the two. Javert closes in. The reader learns the story of the nun, Sister Simplace, who “was gentle, austere, well-bred, cold, and had never lied.” Valjean and Cosette flee with Javert close behind. Questioned by the police, “Did you see Valjean?” Sister Simplace thinks of her lifelong dedication to truth and answers, “No.” Are “little white lies” all right when someone you love is threatened or the truth will hurt someone? A resounding yes from this reader’s corner. Good will win out.

Babe The Gallant Pig, by Dick King-Smith (1983, Britain, 2001 U.S.)

To begin, Farmer Hoggett brought Babe to his farm as a piglet. Like other pigs before him, Babe was slated to be killed for food when in his prime. Hoggett revises his view on slaughtering animals after he witnesses Babe in action, re-trained as a gentle “sheepdog” herder. Not a tale about vegetarians versus meat-eaters, although that underlies the theme, the book does ask, “Are animals simply dispensable? Or do animals have feelings, too, and can they benefit humans in ways other than served up on a platter?”

Hoggett at one point falsely accuses Babe of attacking the sheep and decides to shoot him but learns the truth and spares Babe’s life. Changes for the good occur in Hoggett’s attitude about the worthiness of Babe as a contributor to society and the farm. A newfound attitude of kindness toward creatures slowly takes hold of him against preconceived stereotypes. At a sheep-herding competition where Babe herds the sheep and they quietly follow the pig’s lead, Farmer Hoggett memorably bestows upon Babe the highest praise, saying “That’ll do, pig. That’ll do.” We can easily read into Babe greater respect for the worthiness of all living creatures. That’s a good thing. Since reading Babe, pork is off the table for me.

A Tale of Two Cities, by Charles Dickens (1859)

“It is a far far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far far better rest that I go to than I have ever known,” says Sydney Carton in one of the most famous and recognized lines in any English language novel. This dissolute man who describes himself as “worthless,” in the end switches places with his imprisoned “double,” Charles Darnay, to die in his place. Through Carton’s ultimate sacrifice, Darnay and Lucie Manette, his professed love, can marry and live in peace. At last, Carton will achieve self-worth and even redemption. Indeed, a heroic final act for the greater good.

The Lives of Others (a German film directed and written by Florian Henckel von Donnermarck, 2006)

Set in 1984 in Communist East Berlin, the film revolves around Stasi officer Gerd Wiesler, code name HGW XX/7, whose job requires that he monitor anti-government playwright Georg Dreyman and his actress girlfriend, Christa-Maria Sieland. Over the course of the story, Wiesler learns that freedom has its rewards and that the lives and loves of those who object to the regime in power are far better than his. He changes course and the story becomes his subterfuge in aid of the couple. Wiesler’s obstruction and thus transformation lead to his demotion and firing. He never tells anyone what he has done in the name of goodness over evil. The Berlin Wall and the East German government fall.

Years later, now a postman, Wiesler looks into a bookstore window, sees the featured book, Sonata for a Good Man, and recognizes the face of the author, Georg Dreyman. He goes inside, picks up the book, and opens it to the dedication. “To HGW X/7, in gratitude.” Dreyman had uncovered Wiesler’s secret nobility. Wiesler purchases the book. The bookseller asks, “Is this a gift?” He answers, “No, it’s for me.”

In the darkness of the theater, the audience experienced the proverbial “you could have heard a pin drop.” I know. I viewed the movie the following week also, and numerous times thereafter. But you hear the good-from-bad loud and clear each time.

From Good Intentions to Bad Behavior

Romeo and Juliet, by William Shakespeare (1594-1596)

Herein, we enter the “no man’s – or woman’s – land of bad behavior, the gray area with no malice intended. Yet the consequences are fatal, nonetheless. Friar Laurence becomes the go-between in Romeo and Juliet’s star-crossed romance. The Friar marries the couple despite his knowledge of the virulent feud between their families. The situation worsens when Romeo kills Tybalt and is thus banished from Verona by a royal decree that prohibits dueling. Through the Friar’s machinations and frankly, meddling, the “die is cast.”

Juliet takes a “potion” the Friar gives her to feign death on her scheduled wedding day to Paris, which would be bigotry. Romeo does not receive the letter Friar Laurence sent by messenger about Juliet’s pretend death and too late he finds Juliet “buried” in the Capulet crypt. Romeo drinks poison, taking his own life. Juliet awakens, finds Romeo dead, stabs herself with his dagger, and perishes. Still, there is no doubt that Friar Laurence gave the couple the tools to facilitate this awful scenario. Inadvertent, perhaps, but in actuality, he was not an innocent bystander to the tragedy.

On March 5, 2022, Berkeley School of Law presented UC Shakespeare Trial of Friar Laurence. In the mock trial, Dean of the Law School, Erwin Chemerinsky prosecuted the Friar for the deaths of teenagers Romeo and Juliet. Bernadette Meyler from Stanford Law School served as defense counsel for Friar Laurence. The verdict (from the audience at home and on Zoom) was guilty as charged.

From Good to Bad … to Evil

The Picture of Dorian Gray, by Oscar Wilde (1891)

From pseudo-good or not-so-bad according to society’s dictates, Dorian Gray, at least as reflected in his exquisite face and physique, has his picture painted by Basil Hallward to capture his youthful beauty. Knowing that this beauty will fade with time, he expresses the desire to “sell his soul” and remain eternally young and handsome. He begins a hedonistic downtrend to debauchery and crime, every evil transferred to the portrait, which becomes monstrous. Dorian stabs the painting, a reflection of every ignominious action he took during his life. He then suffers a horrendous death.

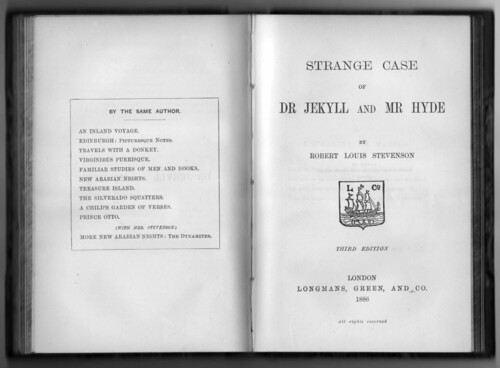

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson (1922-23)

Here is an odd morality tale that shows that each of us has good and evil within us. We are capable of anything. The completely good Dr. Jekyll conducts an experiment whereby he becomes a split personality, good as the doctor and evil incarnate as the debauched Mr. Hyde. Eventually, the evil self takes over and wreaks havoc that the good Dr. Jekyll can no longer control. Only death can bring down the evil Mr. Hyde, but so, too, leads to the demise of Dr. Jekyll. Who triumphs ultimately?

Books and other works of art battle endlessly with this theme, the good and bad (or worse, evil) in us all. Do we grapple with both? Are we capable of anything, depending on the hand we are dealt? Is life a morality play, an endless entanglement? A “wait and see” to witness which surfaces, which sinks, and which wins out? The denouement depends on the extenuating circumstances and the mindset of those involved.

The answer to the age-old question, “What is good, what is bad, and how close behind is evil?” remains enigmatically ambiguous.

One last question of a similar nature fascinates me. “Are you a good witch or a bad witch?” Glinda asks Dorothy in L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz (1900). Think about your own beliefs before you answer.