by Jas Faulkner

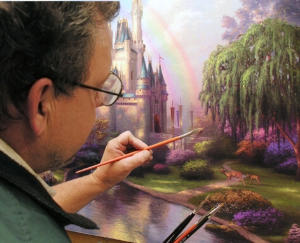

When the news came out that an inebriated Thomas Kinkade had urinated on a Winnie the Pooh statue that was standing in a corner of his suite at a Disney-owned resort, I raised an eyebrow, but shrugged. I had once stayed at a Disney-owned resort in Florida a few years back and left thinking I had a better handle on what it was like to stay in a posh re-education camp for slightly harmless deposed dictators. It had the veneer of comfort, but twenty-four hours in, all I wanted to do was swear, eat greasy BBQ, and pick fights with Yankees fans. That he was driven to let loose all over a representation of one of The Mouse’s more saccharine characters while shouting, “Take THAT, Uncle Walt!” said more about Kinkade than the catalog of Thomas Kincade gifts that would be associated with his name. Among other things, it said Kinkade, who was already known to paint with a sensibility meant to appeal to those who declared themselves “in the world but not of it” was actually quite human and had not lost his ability to sense the absurd.

When the news came out that an inebriated Thomas Kinkade had urinated on a Winnie the Pooh statue that was standing in a corner of his suite at a Disney-owned resort, I raised an eyebrow, but shrugged. I had once stayed at a Disney-owned resort in Florida a few years back and left thinking I had a better handle on what it was like to stay in a posh re-education camp for slightly harmless deposed dictators. It had the veneer of comfort, but twenty-four hours in, all I wanted to do was swear, eat greasy BBQ, and pick fights with Yankees fans. That he was driven to let loose all over a representation of one of The Mouse’s more saccharine characters while shouting, “Take THAT, Uncle Walt!” said more about Kinkade than the catalog of Thomas Kincade gifts that would be associated with his name. Among other things, it said Kinkade, who was already known to paint with a sensibility meant to appeal to those who declared themselves “in the world but not of it” was actually quite human and had not lost his ability to sense the absurd.

It also occurred to me at the time that he might not live much longer.

Outrageous acts like that are usually a precis to either a creative rebirth or a long slide down. Unfortunately for Kinkade, the latter would prove to be the case. Accusations would fly about fiduciary malfeasance, multiple exposés of his works as farmed out affairs would further dilute any question of his value and ability as an artist. By the time of his death, his name had become a pop culture shorthand punchline for everything that was wrong with the mercantile end of creative enterprise.

Outrageous acts like that are usually a precis to either a creative rebirth or a long slide down. Unfortunately for Kinkade, the latter would prove to be the case. Accusations would fly about fiduciary malfeasance, multiple exposés of his works as farmed out affairs would further dilute any question of his value and ability as an artist. By the time of his death, his name had become a pop culture shorthand punchline for everything that was wrong with the mercantile end of creative enterprise.

Associates of Kinkade are already painting unflattering portraits of him as a pretentious teen, God-bothering grifter, and hypocrite  with a yen for porn. Let’s take a look at these points. First, all creative teens are pretentious. It is through pretension that they learn to imitate their betters and eventually develop their own voices. The poets discover Ginsburg and Plath and scribble their own howls of anguish before they find deeper, more challenging writers and other ways to express themselves. The musicians deify Morrison and Cobain. The painters drip their own blood into their mixing cups, watch movie bios of Pollack and Khalo over and over and eventually realise they have just as much to learn from Nicholaides. As adults, we have an obligation to offer an eyeroll and forgiveness as they grow out of it.

with a yen for porn. Let’s take a look at these points. First, all creative teens are pretentious. It is through pretension that they learn to imitate their betters and eventually develop their own voices. The poets discover Ginsburg and Plath and scribble their own howls of anguish before they find deeper, more challenging writers and other ways to express themselves. The musicians deify Morrison and Cobain. The painters drip their own blood into their mixing cups, watch movie bios of Pollack and Khalo over and over and eventually realise they have just as much to learn from Nicholaides. As adults, we have an obligation to offer an eyeroll and forgiveness as they grow out of it.

Grifting for Jesus was probably the worst of his sins. It echoes the generalised greed that runs through this business. Everyone wants to make money on the backs of artists, who are in turn expected to shoulder the costs in terms of time, education, materials and talent. Yet they are often the last considered when art comes down to dollars and cents. Like writers, who can go a long time, sometimes forever, before seeing any money from the works that are published, artists are the last and least considered. On average, galleries take sixty to eighty percent when a piece is sold. I am in no way excusing Kinkade for his conduct. This is an attempt to show the business landscape that creative professionals must navigate in order to make a living. More on that in a minute.

He liked porn. I just can’t get too worked up about this. He was an adult who presumably enjoyed looking at naked consenting adults doing what we are all naturally wired to do. Aside from the fact that porn is kind of boring (a sin in itself), why is this anybody else’s business?

Nobody who decides to become an artist starts out thinking, “I’m going to whore out my talent and grab as much money as I can without regard to the financial security of anyone who backs me or the sensibilities of anyone who might be influenced by what I do.” A creative life starts out as a spark that catches. It can be the ability to tell stories. It can be the moment when you recognise that the smell of oil pastels or the cerebral tickle of finding the right phrase is what moves you. It’s creative the act itself that takes precedence. Anything else is just a detail. Early in a person’s creative development, so much energy goes into gathering the skill sets necessary to perform, little consideration is ever given to the business end of what is going to happen in the future. At worst, writers and artists are told (and told and told) that they can expect to be allowed to do what they do because it is a privilege and they should be happy to use their craft for little in the way of appreciation, much less renumeration. This is the challenge all artists face if we want to make a career of what we love. Thomas Kinkade thought he found a way around this.

Nobody who decides to become an artist starts out thinking, “I’m going to whore out my talent and grab as much money as I can without regard to the financial security of anyone who backs me or the sensibilities of anyone who might be influenced by what I do.” A creative life starts out as a spark that catches. It can be the ability to tell stories. It can be the moment when you recognise that the smell of oil pastels or the cerebral tickle of finding the right phrase is what moves you. It’s creative the act itself that takes precedence. Anything else is just a detail. Early in a person’s creative development, so much energy goes into gathering the skill sets necessary to perform, little consideration is ever given to the business end of what is going to happen in the future. At worst, writers and artists are told (and told and told) that they can expect to be allowed to do what they do because it is a privilege and they should be happy to use their craft for little in the way of appreciation, much less renumeration. This is the challenge all artists face if we want to make a career of what we love. Thomas Kinkade thought he found a way around this.

I don’t agree with his choices, but I recognise where those impulses might have come from.

I am not sure what I would have done if faced if the same dark bargain for the soul of my work. I don’t think any of us really know what  we would do if we were going about our business and it occurred to us that there was a way out of the cycle. All it takes is one night at a gallery and one person too many to walk up and ask you the point of what you do for those dark thoughts to come forward unbidden. The moment the label hits: “just an artist” “just a writer” “your little thing you do” it hits hard. I can’t help but wonder if Kinkade heard statements like that more often than he should, causing him to get cynical.

we would do if we were going about our business and it occurred to us that there was a way out of the cycle. All it takes is one night at a gallery and one person too many to walk up and ask you the point of what you do for those dark thoughts to come forward unbidden. The moment the label hits: “just an artist” “just a writer” “your little thing you do” it hits hard. I can’t help but wonder if Kinkade heard statements like that more often than he should, causing him to get cynical.

Even though Kinkade represents the antithesis to much that I stand for, like Wendy Wasserstein’s Alice, I find it hard to believe there is not another side to him. Interesting wrinkles exhibited at Disney notwithstanding, it turns out that he donated money to primary and secondary schools so they could keep their programs going. He funded scholarship programs so young artists would have the opportunity to learn their craft. He made contributions to museums and libraries. Somewhere among the hackwork and insane marketing was that lost person who at one point, wanted to be an artist.

It is so easy to condemn the sell-out, the author or artist or singer who seems to be laughing all the way to the bank. The perception, the easy conclusion is they have shut themselves away from that still smalll voice that drove them to create in the first place. The fact that Kinkade was abusing his body and had to die at such a young age is a strong indicator that he was still hearing that muse, but no longer knew how to answer. His addiction to the money that came with the denial of his calling was stronger. In reality, it wasn’t the shell of a once creative person that we lost, it was the artist he might have been.

Thanks for the balanced, well thought out assessment, of a man and the path he stumbled upon and then chose to follow.

It is all too easy to despise our own weaknesses when we observe them in others.

Thanks! It seems like the fear and loathing that is being piled on Kinkade is borne of more than just aesthetic outrage. Looking back on this essay, I can say that it would have been harder to write if he’d been someone I admired or whose work I enjoyed. This isn’t the first time I’ve decided to write about someone and ended up having far more sympathy for them that I’d expected.

Nicely put. I’m mocked by my family for liking his work, but, really, the things he did that aren’t the same as all the rest are actually quite good – I suppose they’re just not what appealed to the masses.