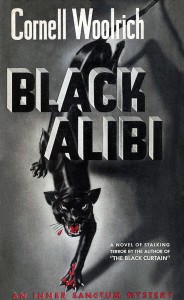

Black Alibi— Cornell Woolrich–1942–used

Black Alibi— Cornell Woolrich–1942–used

The Leopard Man played on Turner Classic Movies yesterday. It’s a must see, again, film. Atmospheric, and in some parts, downright suspenseful and terrifying, it cannot hold a reader’s breath, the way the original source does, Black Alibi. I’ve proclaimed it before, Cornell Woolrich in all his various nom de plumes is my favorite writer, period. Not just favorite crime writer, but writer, of fiction. Yes, that means I like his work more than Dickens, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Poe, Collins, Steinbeck etc., ad nauseum. Is he a finer writer? By most standards, probably not. To mine, yes. Because he delivers life at its most frightening, vulnerable, frantic. Hysteria is never far from breaking out in little pustules–here and there–in one of his novels. Fear is attempted to be kept at bay, yet finds its insidious way back into a character’s life, sometimes as an expected guest, others as a stranger wreaking disaster. Black Alibi is a series of horrific events in separate stories, all part of the larger novel. It begins with U.S. citizens, Jerry Manning, and Kiki Walker finding small success in the South American city of Ciudad Real. Kiki is a headliner entertainer at a local club, and Jerry, her manager. He thinks up a wild idea for publicity, accent on wild. He convinces Kiki to lead a black jaguar into the club for shock and awe, which in turn shocks the jaguar to escape into the night in the city. Each subsequent chapter follows a young woman as she is stalked as prey by what appears to be the missing jaguar. And it’s within these stories Woolrich’s best work is revealed.

Pre-teen Teresa Delgado, is forced by her mother to venture out into the twilight city for charcoal. She’s heard about the jaguar, and is afraid, wants to stay home, but her mother will have nothing of her fear and Teresa is forced not only to go into the streets but travel across the city because the local market is closed. Upon the return trip, she senses a menacing presence and racing to her home, she screams to be allowed in. Her mother meaning to teach Teresa a lesson, delays releasing the lock on the door until too late. All that is left of Teresa are tattered clothes among ripped flesh. Certainly the jaguar was responsible for this tragedy. Manning is considered a villain for bestowing such a menace to the city and the police are not shy in making him view the results of his foolishness, the remains of Teresa.

The reader has become Teresa during the chapter, the terror building along with hers, the frantic demand to be allowed in, part of their own primal fears. If you, as the reader think the worse is past, the next chapter destroys that illusion quickly. In a Woolrich novel, the reader never knows if a character will survive. He is relentless when it comes to building suspense around a likable individual in his story. His best work in this regard is the chapter about a young girl in love with a suitor she hasn’t introduced to her mother for fear of rejection. She meets her love secretly in a walled cemetery, on the pretense of setting flowers on her father’s grave. This particular day she is late, and misses her assignation. Still, she waits, hoping he’ll return. Darkness falls, and she realizes she’s been locked in with the dead. The stories swirling around the wild beast fill her senses as time inches by. She panics, runs to the cemetery wall, screaming for help.

“She walked rapidly down the somber avenue, through an eerie landscape fast dimming in the twilight. Eerie because it was neither natural nor human; it was that of the other world. There was a classical severity to it, a cold melancholy, that nature lacks. These cypresses, poplars, weeping willows, artfully disposed here and there, singly and in copses, they were rooted where dead human beings lay. They touched death, they sheltered it, they even lived and were nourished upon it. And scattered all about under them, through every opening in their low-hanging branches, in every space between their trunks, down every vista and at every turn, was a silent, soulless population, gleaming white in the wavering shadows. A population that seemed to be waiting for some necromantic signal in the depths of oncoming night to come to swarming, malignant life. A population of angels, phoenixes, griffins. The very marble benches here and there along the paths, they seemed to be put there not for the living to rest upon during the course of their visits, but for the use of unguessed shrouded forms flitting along these thoroughfares and lanes in silent passage late at night.

And over it all hung a violent pall of expiring light, the crepusculo, whose very name was a little death in itself. The death of day.”

As we are swept along in her agony, we are hoping, and maybe even saying a little unconscious prayer, that Conchita makes it out alive.

Jerry comes to the conclusion the jaguar isn’t responsible for the attacks–he believes a psychopathic human is. Unable to convince the local police he finally takes fate into his own hands to catch the killer.

There are more cat and mouse maneuvers before the concluding chapter with it’s usual Woolrich stitching together of plot points. Woolrich isn’t known for his logical outcomes as he is for the trip through. He can also seem melodramatic in tenor. It’s those flaws that keep many from proclaiming him to be a great writer. We who appreciate his genius, ignore some of the weaker points, because the larger picture is far far superior to most of the drivel written disguised as fine art. Black Alibi’s level of atmospheric suspense cannot be understated or duplicated. And there’s not a melodramatic pause any place in the story. This book is his best effort within those criteria. His work is alternately dark, morbid, hopeless, and joyfully triumphant. Which end prevails is the mystery, and well worth reading everything written by him, just to find out.

1 thought on “Black Alibi–Best 100 Mysteries of All Time”

Comments are closed.